Over the last decade, AidData, the International Aid Transparency Initiative, and other international actors have tried to put more data about foreign aid flows into the hands of both international actors and common citizens. These organizations argue that giving this information to citizens in the developing world will help those people hold their governments more accountable.

A long-running argument in the development literature, however, proposes that information about what the state is not doing might undermine the legitimacy of governments in developing countries. That is, if people believe that their own government should be funding health and education systems, they might react poorly when they find out that the resources for these public goods are coming from outside of their country.

We have been collecting data on this question in a series of surveys, and so far, we have found little evidence that information about foreign aid is undermining domestic government legitimacy. Indeed, we instead have found some evidence that it may improve people’s attitudes toward their governments.

India

As described in an article published earlier this year in the Journal of Experimental Political Science, in 2012, we fielded an online survey in India in which we described an HIV/AIDS project. Every respondent to our survey was randomly assigned to read one of five different descriptions of the project. While most of the information was the same across the five versions of the survey, we varied one sentence about who was funding and implementing the project. In three versions of the survey, we noted that the United States had provided funding; in a fourth version of the survey, we instead spoke about Canada’s role in funding the project; while in the control version of the survey, we did not mention any external funding. For two of the versions of the survey where the United States was named as the funder, we described the project as being implemented either by an international NGO or a local NGO.

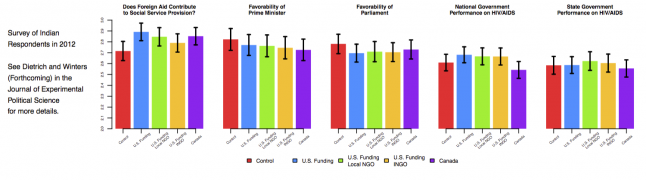

Results from Online Survey in India (Click to expand chart)

We found clear evidence that people absorbed this funding information when taking the survey: across three of the four versions of the survey where respondents heard about foreign funding, they were subsequently more likely to say that foreign aid contributes to the provision of social services in India. This updated information, however, did not make them change their opinions about their own government. Whether asked about the general performance of the prime minister or the parliament or the issue-specific performance of the national or local government in the domain of HIV/AIDS, our respondents who heard about foreign funding of the project answered the questions in a way that was statistically indistinguishable from how our respondents in the control group answered the questions.

Bangladesh

In 2014, with Minhaj Mahmud from BRAC University, we ran a similar informational experiment in Bangladesh. In a nationwide, face-to-face, household survey, each of our respondents watched a one-minute video about a system of health clinics that serve poor areas in Bangladesh. Half of the respondents watched a version of the video that linked the health clinics to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and also were then told that the U.S. had been funding the health clinics for over 15 years.

Once again, we found that people’s attitudes toward the national government were indistinguishable whether they had been told that the United States provides funding for the clinics or not.

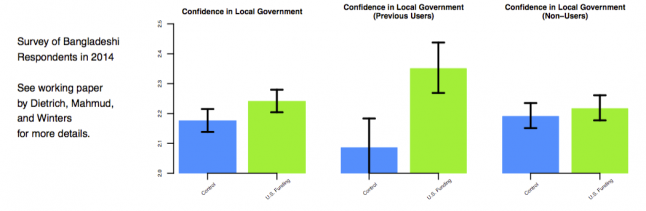

Results from Survey in Bangladesh (Click to expand chart)

In the Bangladesh data, however, we observe a small but statistically significant increase in people’s opinions toward their local government when they learn that the clinics have been funded by the United States. And interestingly, this increase is particularly concentrated among the 25 percent of our respondents who report having used the clinics!

These results suggest that Bangladeshis give credit – perhaps undeserved credit – to their local governments for securing foreign aid funds for social services. We plan on doing additional survey work in the future to learn more about how citizens assign responsibility for the provision of social services and how they think about foreign funding of such services. For now, we are confident that our results – along with those produced by scholars like Jennifer Brass (in her book manuscript NGOs and the State in Development) and Audrey Sacks (in her World Bank Policy Research Working Paper “Can Donors and Non-State Actors. Undermine Citizens' Legitimating Beliefs?”) – provide little evidence that informing citizens in developing countries about foreign-funded provision of development interventions and social services undermines their perceptions of their own government’s legitimacy.