Easterly opposed bed net distribution. [The World Bank] rejected Easterly's advice, and cut malaria sharply. Yes, debate's over. Aid works! —Jeffrey Sachs, 2014

The big aid debate that Sachs initiated is now really over… His idea that aid could achieve rapid development and the end of poverty was wrong, and it's time to move on. —William Easterly, 2013

According to scholars on both sides of the health aid debate, the debate is over. Those who declare that health aid works and those who maintain that health aid fails both claim consensus. How can this be?

Macro-level studies largely condemn health aid as ineffective or minimally effective in the aggregate (see Williamson 2008; Gebhard et al 2008; Wilson 2011; Mishra and Newhouse 2007). Conversely, most of the praise for health aid comes from project-level analyses (see Demombynes and Trommlerova 2012; Fegan et al 2007; Du Lou, Pison, and Aaby 1995). It may be time to rethink the way we’re analyzing these relationships.

Sub-nationally geocoded development data produced by AidData allows for a new approach, one of analyzing aid at a level above projects but below the country as a single unit. More specifically, it allows for examining both health aid in smaller geographic units but also as a whole, without aggregating aid amounts to a single number as cross-national studies do. Geocoded data shows not only where aid is allocated, but also where it is not. When paired with geo-referenced household survey data, evaluation of aid distribution and impact become possible within a county.

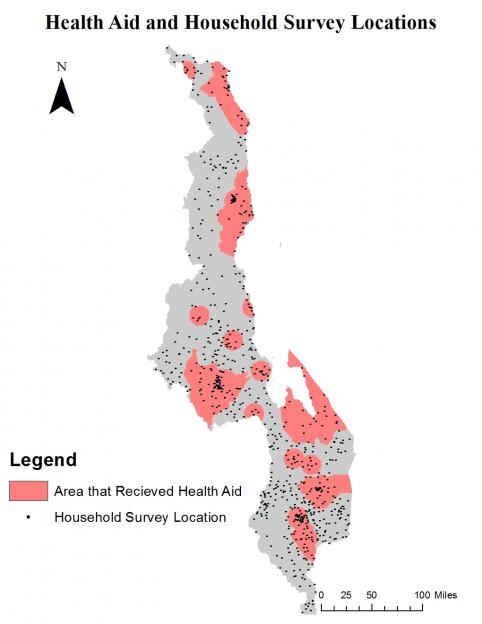

Map showing respondents from Malawi’s household survey who were in areas where health aid projects were completed in 2008.

What is the relationship between the allocation of health aid and its impact at the sub-national level? I conducted my own analysis using 2005-2010 geocoded data from Malawi’s Aid Management Platform provided by AidData and socio-economic data from Malawi’s Third Integrated Household Survey, conducted in 2010 and 2011. I used logistic models to examine the determinants of aid allocation and propensity-score matching techniques to assess the average impact of this aid. This analysis included consideration of four time periods, two definitions of aid (a narrow and broad definition, specifically projects purpose coded as health aid, and projects with either a health purpose code or activity code), and three ‘aid impact zones’ for aid projects given to a specific location (5-mile, 10-mile, and 15-mile radii).

Does health aid go to those most in need? In Malawi the results are mixed. The allocation of funding varies by year in terms of whether it was given to those with the poorest health conditions. In general, aid appears to be going to more populated areas and, in all but one year, poorer areas are less likely to receive aid than their wealthier counterparts. However, this does not necessarily mean that aid is allocated poorly. For example, poor conditions are pervasive throughout Malawi, and giving aid to population centers, where people are relatively better off generally but where many poor people also reside in concentrated numbers, may enable aid to have more “bang for its buck.” The results do raise questions, however, about the effectiveness of aid allocation.

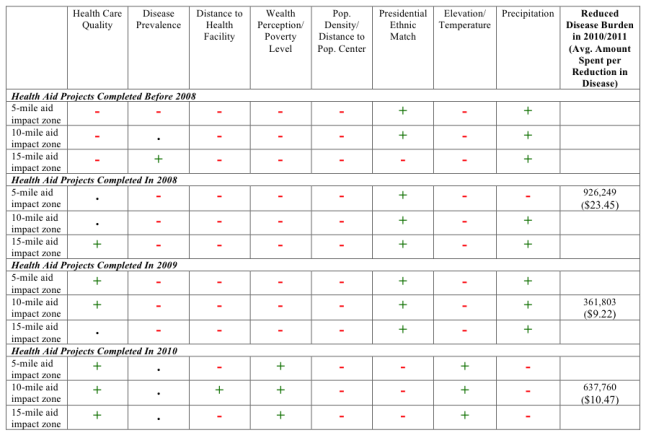

Allocation and Impact of Purpose-Coded Health Aid

Plus / minus signs indicate effective / ineffective aid allocation (‘effective’ defined as aid going to areas most in need), whereas a dot indicates the variable was not important. Reduced disease burdens are reported when treatment effects were significant at the 95% confidence level. Pluses are given when aid is associated with: worse health care, higher disease prevalence, greater distance from a health facility, more impoverished areas, greater distance from a population center or less population density, not a presidential ethnic match, lower elevations or higher temperatures (greater risk for malaria), and more precipitation (greater risk for vector and waterborne diseases).

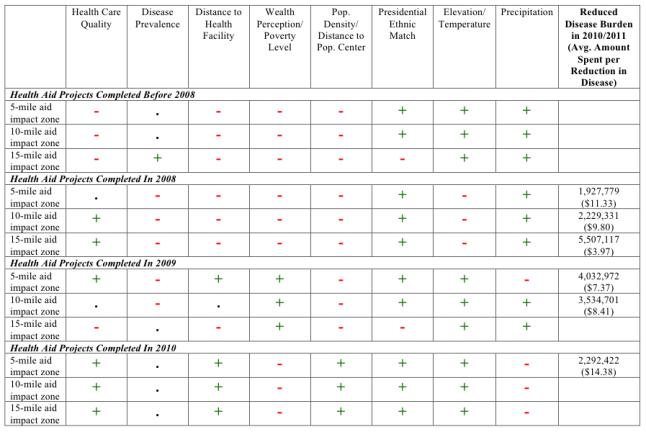

Allocation and Impact of Purpose and Activity-Coded Health Aid

Plus / minus signs indicate effective / ineffective aid allocation (‘effective’ defined as aid going to areas most in need), whereas a dot indicates the variable was not important. Reduced disease burdens are reported when treatment effects were significant at the 95% confidence level. Pluses are given when aid is associated with: worse health care, higher disease prevalence, greater distance from a health facility, more impoverished areas, greater distance from a population center or less population density, not a presidential ethnic match, lower elevations or higher temperatures (greater risk for malaria), and more precipitation (greater risk for vector and waterborne diseases).

Even though aid is not consistently given to less well off areas of the country, health aid in all years of study since 2008 significantly reduces disease burdens among those surveyed in 2010/2011. My estimates suggest that yearly aid is related to a decrease of 300,000 to 5 million cases of illness and is relatively cost effective—costing between four and twenty-three dollars per case.

These estimates are sensitive to the definition of health aid and assumptions regarding the extent to which aid has an impact beyond the specific project location (see tables above). For example, results suggest that purpose-coded health aid is associated with a decrease of 640,000 cases of illness, on average, while purpose and activity-coded health aid is associated an average of 3.2 million cases of illness.

This analysis suggests significant aid impacts that stand in contrast with theories that suggest that the fungibility of aid could explain why the observed impacts of aid stop at micro-level analyses. Notably, sub-national analysis, showing areas that received aid to be better off (all other things being held constant), supports the positive impacts of aggregate aid. This suggests that country-level data—that fail to find notable aggregate impacts—may be too blunt.

These findings don’t help adjudicate between those who agree with Sachs that aid can help drive development and those, such as Easterly, who argue that aid “benefits some of the people some of the time,” but they do contrast with cross-country studies that find no impact whatsoever.

The results also stand in contrast to Claudia Williamson’s claim that “[t]here is a lack of evidence to indicate that health aid should be pursued as a policy objective.” Sub-national analysis provides evidence of health aid impact. But does this warrant the exclamation that Sachs gives? “Yes, debate's over. Aid works!” No. The sub-national results suggest that aid can work. The real question is when and to what extent it works.