Saudi Arabia has just ended a month-long bombing campaign in Yemen to hold off advancements by the Houthi rebels that threaten to take over the country. This forceful show of hard power is rather uncharacteristic. Historically, Saudi Arabia has relied on soft power to bolster its neighbors, increase regional stability, and provide support to the political powers it deems friendly. One important source of this soft power is the Saudi’s deep pockets for development finance, of which Yemen has been a significant recipient over recent years. The Saudi’s have announced the next phase of its operations after the bombing campaign will switch back to the much-needed development and humanitarian aid. But what has this aid looked like in the past?

When Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh resigned in February 2012 after a year of public pressure, Saudi Arabia and a coalition of other international and regional powers committed to providing extensive financial assistance to stabilize the new transitional government. At the 2012 “Friends of Yemen” conference in Riyadh, international donors pledged over $6.4 billion to the new government, with Saudi Arabia offering almost half of total pledges. However, a lack of consistent aid reporting practices from donors like Saudi Arabia has limited the ability of international observers to monitor how much of this assistance Yemen has actually received or what was funded under these blanket pledges.

Last year, AidData applied its Tracking Underreported Financial Flows (TUFF) methodology, previously used to estimate Chinese official financing in Africa, to fill this critical information gap on Gulf Cooperation Council donors. The end result is a dataset of 491 aid and official finance projects from Saudi Arabia and Qatar to 22 recipient countries in the Middle East and North Africa. Similar to our work tracking Chinese official financing in Africa, the GCC dataset combines publicly available donor and recipient reports on aid flows with media reports and academic articles to estimate aid from Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Furthermore, with this data researchers can sub-nationally geo-reference Saudi and Qatari aid projects.

Diving Into the Data

So, what does the data show us about Saudi Arabia’s support to Yemen in the years preceding and following the resignation of President Saleh?

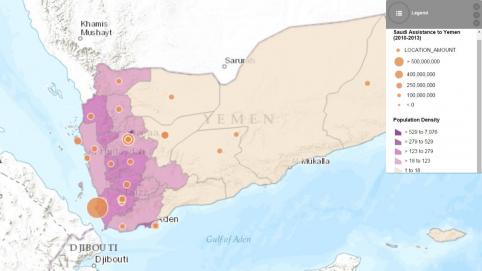

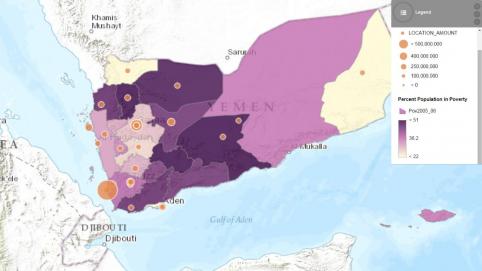

First, the sub-national distribution of Saudi aid in Yemen appears to be directed toward areas of highest population density rather than areas with the highest ratio of people in poverty. One interpretation of this finding is that the influx of Saudi funding in 2012 and 2013 was meant to promote short-term stability rather than long-term poverty alleviation (see figures 1a and 1b).

Figure 1a. Click the image for an interactive version of this map.

Figure 1b. Click the image for an interactive version of this map.

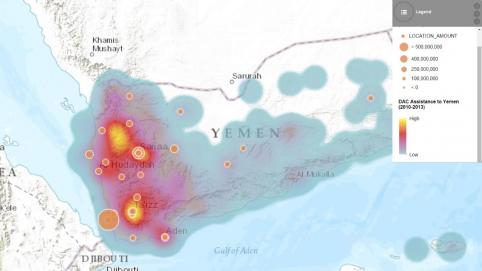

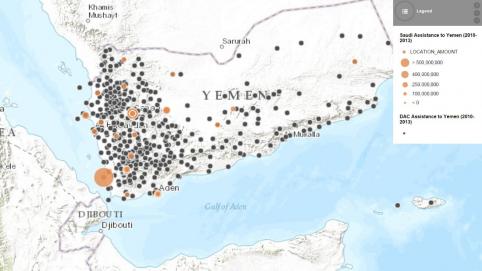

Second, there appears to be a high degree of convergence between where the Saudis and Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors targeted their aid (see Figures 2a and 2b). In both cases aid is concentrated in Western Yemen, particularly around the region’s major population centers.

Figure 2a. Click the image for an interactive version of this map.

Figure 2b. Click the image for an interactive version of this map.

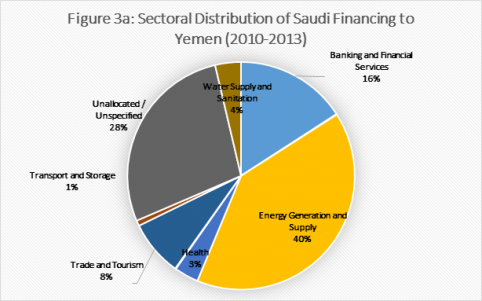

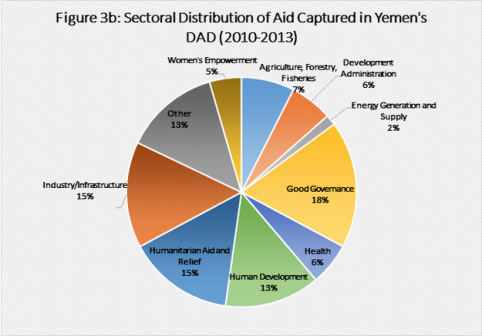

Third, while the total volume of Saudi support committed to Yemen was large—ranging from $4.8 billion to $6.3 billion between 2010 and 2013—the focus of that financing did not prioritize government capacity building, based on a look at the distribution of aid by sector (see Figure 3a). Rather it was predominantly budget support, in-kind fuel donations and funding for infrastructure projects. The distribution of Saudi aid to Yemen stands in sharp contrast to aid from Western donors over the same period (as captured in Yemen’s Development Assistance Database). As shown in Figure 3b, Western donors directed a much larger portion of their aid to governance and human development projects. This suggests that Saudi Arabia’s comparative advantage in aid delivery, relative to Western donors, is in its willingness to quickly make large amounts of capital and fuel available to its allies. Note: The large amount of unallocated/unspecified aid is a result of a $1.75 billion pledge for undefined “development projects” made by Saudi Arabia at a “Friends of Yemen” conference.

Figure 3a

Figure 3b

Yet, while Saudi Arabia was willing to make this money available, it may have been too difficult to deliver. TUFF data tracks commitments and not disbursements. Given Yemen’s instability and poor delivery mechanisms, it is possible that much of the aid promised was not delivered. This would be consistent with total official development assistance reported via the OECD’s DAC, which shows that disbursements of aid to Yemen went drastically down in 2012, likely due to distribution/delivery problems.

What's Next?

What lessons will Saudi Arabia and the West take away from Yemen’s recent coup, in light of their past investments in Yemen’s stability? The combination of Saudi Arabia’s capital and Western logistical support and capacity-building efforts appear to have been insufficient to stabilize Yemen’s transitional government. After investing heavily and losing with Yemen’s transitional government, will the Saudi regime be more hesitant to provide financial support to fragile states in the future? Should Western donors prioritize capacity building for new or fragile governments? Do contrasting approaches to aid delivery have different development and governance outcomes? Can Saudi Arabia’s approach to development financing complement Western donors or do the work across purposes?

While these questions are beyond the scope of this blog post, we hope the availability of this new TUFF data on aid from GCC donors will catalyze a new wave of research along these lines.