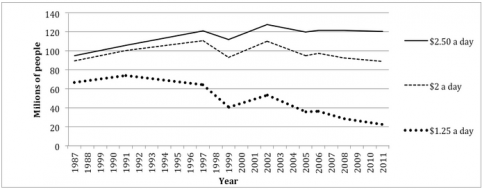

Pakistan has made remarkable progress in reducing absolute poverty. Fifty million fewer people lived in poverty in 2011 than in 1991 and the share of the poor living on less than $1.25 a day plummeted from 66.5% in 1987 to 12.7% in 2011. Despite these advances, the number of Pakistanis vulnerable to falling into poverty remains high and the recent series of natural disasters that have hit Pakistan will slow future progress. Pakistan lags behind other lower-middle income countries in non-income determinants of poverty, such as education and health. Can Pakistan overcome these concerns and become the next Asian Tiger in the region?

Impressive progress, yet problems persist

While absolute poverty levels have substantially decreased, more than half of Pakistan’s population – almost 90 million people – was still living on less than $2 a day in 2011.However, the latest income poverty data has raised caution over the accuracy of the 2011 poverty estimates.

Figure 1: Number of poor people in Pakistan, 1987 – 2011

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators. Poverty lines are in 2005 international dollars.

While the number of people living under $1.25 a day plummeted, the number of people living under $2 has barely declined and those under $2.50 actually increased

Income growth and income inequality are key

Income growth in Pakistan has been the main driver of poverty reduction, according to a World Bank report. Pakistan’s Gini coefficient and Palma ratio (the ratio of income held by the top 10% compared to income held by the bottom 40%) have fluctuated over time, but has followed a general downward trend, indicating that income inequality has declined. The Benazir Income Support Program may be partly responsible for this improvement. Unlike its predecessors, the program transfers money to the female head in each household, the idea being to increase women’s empowerment. The BISP significantly increased the amount of social welfare the Pakistani government was spending on the poor. Through a combination of continued economic growth, income support programs and large inflows of workers’ remittances, consumption growth of the poorest 40% has managed to keep pace with the rest of Pakistan’s population in recent years.

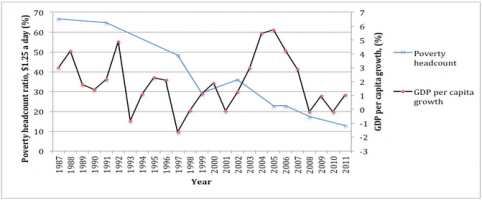

Overall, Pakistan has done well in converting economic growth into poverty reduction (see Figure 2 below). But stronger and more sustained growth is needed to continue reducing poverty in order to reach the poorest of the poor. Equitable income distribution is important, as it can influence the effect of growth on poverty reduction: if income inequality is high, economic gains are more likely to accrue accrue to the wealthy with little left for the poor. If income distribution were more equitable, the poor would gain more from the country’s economic growth, allowing them to consume more and build up enough savings to develop assets such as education and housing.

Figure 2: Poverty headcount ratio and GDP per capita growth in Pakistan, 1987-2011

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators

Differences across provinces have narrowed, but urban / rural differences remain large

Poverty has steadily declined even when income growth was volatile in the 1990s. Growth in the new millennium did not alter the pace of poverty reduction, demonstrating that the responsiveness (or elasticity) of poverty to growth has declined. Going forward, even stronger growth, coupled with direct interventions, may be needed to achieve further falls in poverty.

Provincial poverty data indicate that poverty rates have converged across the country. According to a World Bank report, in 1999, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa had a much higher poverty rate (41%) than other provinces in Pakistan. Next highest were Punjab (30%), Sindh (26%) and Balochistan (22%). The poverty data from 2011 shows a marked improvement: Balochistan province had the highest poverty rate (17.7%), followed by KPK (14%), Punjab (13.7%) and Sindh with the lowest rate (12%).

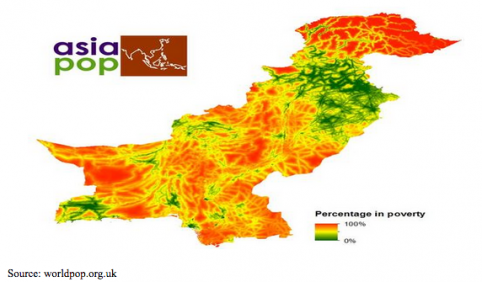

Urban/rural differences remain pronounced, however, with 15% of the rural population living in poverty compared to only 7% of the urban population. On the multidimensional poverty map created by worldpop.org.uk (see Figure 3 below), most green areas (lower levels of poverty) are major towns and cities, while red regions (higher levels of poverty) correlate with mostly rural areas.

Figure 3: Geographic distribution of poverty in Pakistan, 2007

Poor data makes for poor policy

Pakistan has its own national poverty line, measured by calculating the basket of goods that meet the minimum number of calories for an adult. The line is adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index, which does not place adequate weight on food prices, since the poor spend proportionately more on food than non-food items. Pakistan’s Bureau of Statistics does not collect CPI data from rural areas, which means that there is one uniform poverty line for rural and urban households, even if they spend different amounts to meet their minimum requirement of calories. Furthermore, there has not been a census in Pakistan since 1998, meaning the population weights and sample sizes become increasingly imprecise. These apparent flaws in the methodology have led to some skepticism over the Bureau of Statistics’ latest poverty data. The larger issue is that if the government cannot collect reliable poverty data, then it cannot be sure of whether its poverty eradication policies are achieving the desired results.

Non-income measures of poverty – including education and gender parity – are weak

Inequality in Pakistan is much higher in non-income terms. Secondary education completion rates were 26.6% in 2011, up from 18.6% in 1999, but still very low compared to other developing countries with similar income per capita. Gender parity in education is slowly being achieved, though in Balochistan, parity in primary and secondary education fell between 2002 to 2012. At the start of 2015, Pakistan is not on track to attain the Millennium Development Goal for gender parity in education. Moreover, even if improvements in women’s access to education continue, barriers to employment are impeding efforts to lift women out of poverty with only 20% female labor force participation in 2010 compared to 50% for men.

Foreign aid has been massive, but it has not always been well spent

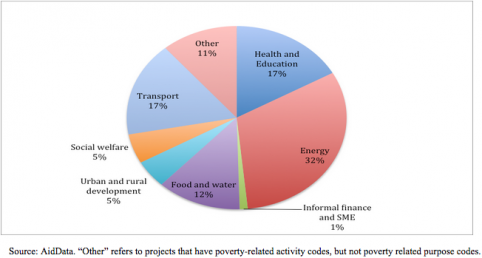

AidData provides geocoded data on aid projects in order to reveal which regions of a country are underserved, as well as aggregate information on the size of aid, foreign direct investment, and remittance inflows into a country. While some of Pakistan’s aid projects have already been mapped, AidData also applies purpose and activity codes to data drawn from the OECD’s Creditor Reporting Systems which allows for a simple comparison of what types of poverty related projects have been prominent (see Figure 4 below).

Figure 4: Total commitments to poverty related projects by sector from multilateral and bilateral donors, 1952-2012 (constant 2011 $)

Cumulatively, the energy sector has been the largest sector recipient of development related aid, which is not surprising given Pakistan’s chronic problems with reliable electricity supplies. Health and education do not get as much attention as they probably should, given their historically poor performance and the likelihood that investment in these two would achieve the biggest payoffs for poverty reduction and economic growth.

Independent evaluation reports from the World Bank and Asian Development Bank have been critical of vast amounts of aid to Pakistan that have been not as effective as expected due to poor planning, misplaced incentive structures and failure to understand how social and institutional norms can impede progress. Moreover, fluctuations in foreign assistance – based largely upon the geostrategic interests of major donors – may have made long-term planning extremely difficult.

Becoming the next Asian Tiger

Although great strides have been made, millions of Pakistanis remain vulnerable to falling into absolute poverty. An external shock – such as a natural disaster – could easily push them back into poverty. Efforts have been made to improve education and health, but results have fallen far short of what is needed. Economic growth has been the main driver of reducing poverty, complemented by large inflows of remittances. However, remittances are not a silver bullet and fiscal pressures may limit the extent of income redistribution. What is needed is sustainable and pro-poor growth: structural reforms to create jobs and growth, and social investment to raise growth and make it more inclusive over the long-term.

The potential benefits are huge, since Pakistan has a large working population and is close to many emerging markets that could drive Pakistani exports. With the right policy mix, a new Asian Tiger might emerge in the coming decades.