Although Cashgate has drawn much attention domestically and around the world, theft of public finances is not a new phenomenon in Malawi. (Here is one example from two presidents ago.) Nor is Cashgate the first episode in Malawi’s history that has prompted donors to withdraw aid in response to government corruption: the International Monetary Fund suspended lending during the Muluzi and Mutharika presidencies in 2001 and 2011, respectively (see Resnick, 2012). But Cashgate is different from earlier donor withdrawals in Malawi in that it has occurred during Joyce Banda’s first term in office, whereas previous lending suspensions occurred during the presidents’ second (and constitutionally final) term in office.

Donor withdrawal of budgetary support obviously cripples Banda’s ability to manage the needs of the country, as roughly 16% of Malawi’s GNI comes from foreign support. Already, civil servants have experienced pay-day delays. The government is short on cash, and has had to drastically cut ministry budgets. Austerity measures have been implemented to control government spending. The last time donors pulled budgetary support in 2011, it crippled local foreign currency reserves, exacerbated Malawi’s economic decline, and directly impacted people in need. As I wrote in an article with Malawian political scientist Boniface Dulani, “Medical supplies, including life-saving antiretroviral treatment for HIV patients, were often out of stock, prompting Malawi’s international partners to intervene by directly importing medicines into the country.”

Donors have pulled out precisely when Banda needs things to go well in order to win the upcoming election in May 2014. Cashgate has eroded public confidence in Banda’s ability to lead the country, but it is unclear whether it is fair to pin the problem on Banda. As I suggested in my post yesterday, technical solutions such as the implementation of Malawi’s Integrated Financial Management Information System have the ability to increase transparency, but it requires political will to investigate the financial discrepancies that come to light. Whereas past corruption prosecutions have focused on political opponents, the current scandal has implicated high-level officials in Banda’s own government and party. Banda may actually deserve the credit she is claiming for exposing this corruption.

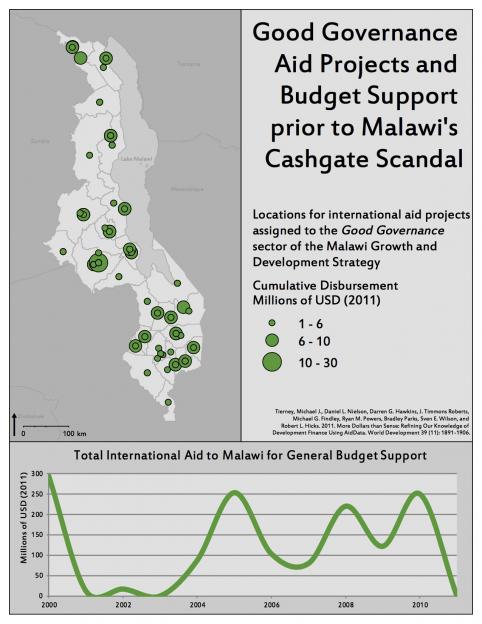

Suspended aid to Malawi (estimated at $150 million) will not resume until there is “clear assurance, independently verified that [donor] resources are all being used for their intended purpose,” said Sarah Sanyahumbi, an official with the UK’s Department for International Development in Malawi. This is one challenge of providing aid as budgetary support rather than program support. Aid to support government budgets shifts control over how money is spent from the donors to the government. When problems arise, budget-supporting donors are left with an “all-or-nothing” option – and in the wake of Cashgate, these donors chose “nothing” by withholding support. The US, which has also been vocalabout Cashgate, has not suspended aid in the wake of the scandal. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) had suspended aid after the initial accusations of graft in the Cashgate scandal, but, following an in-country assessment, the IMF recently announced it would resume its disbursement. The US provides all of its aid via program support, which allows donors to have more control over how funds are spent and thus be more flexible when responding to allegations of misuse of funds.

The adoption of the Aid Management Platform – an aid information management system supported by AidData partner Development Gateway – by Malawi’s Ministry of Finance has increased transparency of where project aid is going (literally, on a map). However, technical fixes do not remove the need for political will on the part of politicians to instigate changes in how public finances are managed. Ground-truthing project aid disbursements is possible, but it depends on civil society organizations in Malawi or other interested parties using the publicly available Aid Management Platform to identify aid project locations and investigate the status of projects.

Contrary to the perspective of analysts who point to civil society as weak in the African context, the current political situation in Malawi has largely been influenced by the actions of those outside of government. IFMIS may, in the end, prove very helpful in identifying public finance misuse. Donor withdrawal and threats of withdrawal have certainly incentivized the government to move swiftly in prosecuting offenders. However, the Cashgate scandal may also be introducing the rest of the world to a more vocal and active Malawian civil society. It’s still to be determined how important foreign aid has been in fighting corruption in Malawi, and even aid optimists should consider the bigger question about how much democratic development came from outside Malawi and how much of the heavy lifting has been done by Malawians themselves.