Over the past few weeks, much media attention has been focused on Japan, as it deals with the aftermath of a massive earthquake/tsunami. The affected areas are clearly in need of both emergency relief and long-term rebuilding. Of course, Japan is far too rich a country to receive aid in the form of official development assistance. Indeed, a lack of money is rather unlikely to constitute a constraint on Japan's response to the disaster: given Japan's near-zero rate of inflation, the government can print just about all the money it will need.

Instead, the primary constraint, as is often the case with natural disasters, appears to be one of infrastructure, logistics, and coordination: there are only so many vehicles available to drive around the area, only so many officials sufficiently familiar with the area, so many places where relief workers can be housed, etc., and all the activities of domestic and foreign organizations need to be coordinated. For this reason, Japan has been very selective in the aid it has asked for from other nations: it has asked for search-and-rescue help from four or five countries and it just recently requested assistance from a French nuclear reactor manufacturer.

Because financial resources are unlikely to be a constraint in Japan's case, people who are moved by the devastation and wish to help would probably do better to look back at last year's earthquake in Haiti and donate to organizations that continue to do crucial work there, after the world media has largely moved on. Whereas Japan is one of the richest countries in the world, Haiti is one of the poorest, and here money definitely is a constraint. Two organizations that do excellent work in Haiti are Partners in Health (PIH) and Doctors without Borders (MSF).

Haiti is also an interesting case study of the challenges involved in trying to make aid work. One year after the quake, hundreds of thousands of people still live in temporary, make-shift camps, and 95% of the rubble remains uncleared, despite massive pledges of aid. Moreover, the slow reconstruction process has made possible a cholera outbreak which so far has taken the lives of almost 5000 people.

(picture from the website of the U.S. mission in Geneva)

A recent report by Oxfam International highlights some of the problems Haiti faces:

- Aid agencies, trying to give aid as directly and effectively as possible, bypass local and national authorities. This undermines the government, frustrates attempts at improving governance in Haiti, and, of course, makes the coordination of aid efforts nearly impossible.

- Aid agencies, including the central Interim Haiti Recovery Commission, rarely consult with the targets of aid initiatives (local civil society)

- Aid agencies are more interested in building new things, to which they can attach their name, than they are in cleaning up, general maintenance, etc. Thus there are plenty of funds earmarked for new buildings, but almost none for the rubble-clearing that needs to come first

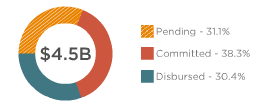

- Not all aid donors live up to their promised commitments. The Oxfam report notes that as of November 2010, only about 40% of the funds pledged to Haiti for 2010 had been disbursed, according to the UN Special Envoy to Haiti. As of today (March 30), the envoy's website shows that about $4.5 billion has been promised, of which 31.1% remains pending, and 38.3% has been committed but not actually disbursed (i.e. made available):

All of these problems are depressingly familiar to anyone who has studied foreign aid in other contexts. Still, moved by the particular urgency of such a massive humanitarian crisis, donors might have been expected to overcome their traditional reluctance to coordinate, listen to their recipient counterparts, and live up to their promises. Unfortunately, long-standing practices are difficult to change, no matter how urgent the impetus.

On an encouraging note, Haiti’s Ministry of Planning and External Cooperation (MPCE) is now implementing an Aid Management Platform (AMP) (funded by aid donors) to facilitate transparent and effective aid management and tracking. AMP will help the government to monitor the performance and alignment of aid and external private and public investments in the context of the official Action Plan for the Recovery and Development of Haiti (PARDH).

It is to be hoped that this will speed up the conversion of pending and committed aid into actual disbursements to help the rebuilding of Haiti. Still even if all promised aid is disbursed, the need in Haiti will remain great, and (as mentioned above) organizations such as PIH and MSF could definitely use additional private contributions.