Farmer taking notes during the June District Dialogue Meeting in Mityana

“One…two…three…four.” I scan the room, counting the number of hands raised to answer to my question. I was about to present maps tracking National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS) budget and service delivery, but I wanted to know something first. Did these farmers realize that they could access detailed information on the government’s agricultural activities and provide feedback? The answer: only 4 out of 100 farmers had even heard of the Uganda Budget Information website.

Transparency advocates point to the Ugandan Budget Information website as a tool of accountability to usher in good governance and evidence of the open data movement gaining ground. Yet, exactly how transparency leads to good governance remains unclear.

Good governance focuses on a process of decision-making that is transparent, accountable, effective, and inclusive. Opening up government data to the public is arguably an essential ingredient for good governance. But is something else missing? If citizens lack the means to actually hold their governments accountable, attempts to foster good governance will likely fail.

This brings me back to the gathering of Ugandan farmers and my presentation on the Ugandan Budget website for the District Dialogue Meeting.

The Ugandan Budget Information Website Falls Short

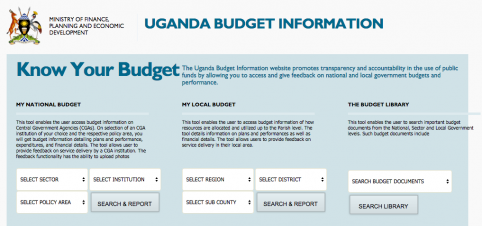

The Uganda Budget Information website proclaims to, “[promote] transparency and accountability in the use of public funds by allowing you to access and give feedback on government budgets and performance.” It discloses descriptions of the planned allocation of funds, the status of its disbursement, and its destination defined at the district level down to the sub-county level. On the whole, the website represents much of what the open data movement advocates for.

Uganda Budget Website screenshot (Source: http://www.budget.go.ug/)

Upon closer inspection, however, the website is a telling example of how transparency can fall short without robust mechanisms to engage citizens. A simple search on the local budget of a particular sub-county reveals a conspicuously empty comment section next to budget details. It would be a mistake to assume that lack of comments is an endorsement for the effective delivery of services.

Ms. Medina’s comments at the June District Dialogue Meeting in Mityana about her experience with NAADS delivery of services is a case in point: “They call us farmers for training meetings and we dutifully attend. They include us as beneficiaries, but we never receive the promised services. Some of us have received repeated promises but in vain.” Other testimonies that day echoed her story. Whether due to insufficient public awareness or limited Internet access, citizens aren’t providing feedback on government services via the website. Local governments sometimes report incomplete financial data and often with a time delay, further compromising the greater goal of disclosing comprehensive data.

Ms. Medina shares her experience with participants on NAADS service delivery in her sub-county

Social Audits, A Potential Remedy?

Social audits, a growing form of civil society activism, may help close this feedback loop between the government and constituents. Social audits are typically community gatherings where local government plans are discussed and citizens can testify about their experiences with public services. Some countries, such as Rwanda, have conducted community radio programs where district officials discuss proposed plans and listeners call in. The overwhelming response to my presentation on monitoring and tracking budget performance also suggests that data visualization and maps can serve as powerful tools for social audits.

For social audits to work, however, three requirements must be met. First, citizens must have access to the information under inquiry. Second, as traditional social audits can entail a review of thousands of government document pages, training, and preparation for community member meetings may be required. Lastly, there must be some legal recourse for evidence of fraud or mismanagement discovered in the social audit.

Despite its flaws, the Ugandan Budget Information fulfills the first of these two requirements, but if evidence of fraud or mismanagement is found, there is often no punitive action taken. With a corruption perception index ranking of 140 out of 177, many question whether this is politically viable in Uganda. The current trend in Uganda is to ‘militarize’ ineffective government programs, as recently proposed as a reform measure to address the controversy surrounding government’s NAADS program. Without incorporating effective citizen engagement in such reforms, however, there is risk that more of the same will continue.

The potential of social audits has already been demonstrated in Rwanda, Kenya, and India. In the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, the first state government to require by law the conducting of social audits, “[officials] embraced the audits in part because they realized it was good politics to keep programs for the poor free from corruption.”

The implementation of social audits could help the Ugandan Budget Information website fulfill its potential as a powerful tool for accountability. Moreover, such audits can help the open data and aid transparency movement make progress toward good governance by giving necessary weight to government publication of information and effective citizen feedback.