“In Nepal, we need to move beyond just talking about open data, and start asking questions like ‘who are the consumers of this data and how are they using it?’ ” said Dr. Sagar Sharma, Chair of the Development Studies Department at Kathmandu University of the Arts.

This past Sunday, Kathmandu University of the Arts, AidData, and the Open Nepal coalitionco-hosted the second Nepal Open Data Working Group in Kathmandu, a continuation of the Working Group held in February of this year. Coming on the heels of the recently unveiled 2014-2015 proposed national budget and new Development Cooperation Policy (DCP) on foreign aid, the discussion centered around two key questions. How can more granular, geo-referenced budget data be used to better understand the allocation and impact of publicly financed projects? And how can stakeholders interact with this data in their communities?

In an animated dialogue with over twenty government officials, media, civil society organizations, academic institutions, and students in attendance, participants discussed the challenge of nurturing a stronger community of data users in Nepal. While everyone agreed that data visualization tools were key to achieve this goal, there was a consensus that the very nature of the data being produced needed to change in order to make it more relevant to target audiences – namely, government officials, civil society groups, and citizens.

“When we are presented with a map of budget or aid allocations, we often try to analyze it from the perspective of an economist rather than a citizen,” explained Bhibusan Bista of Young Innovations, one of the coalition members of Open Nepal and Working Group participants.”

“The only way to close the data supply and demand gap is by focusing on the micro-data that really matters to people, like local information on roads, schools, and hospitals.” Bista cited the example of Check My Schools community monitoring project in the Philippines – a parent-centered website that reports information on teacher attendance and other performance indicators for public schools.

Two of the event speakers, Prakash Neupane of the Open Knowledge Foundation (OKF) and Anirudra Neupane of Freedom Forum (FF), showcased innovative ways in which budget data is currently being used in Nepal. OKF’s Open Spending project, an open database of public financial information, is mapping disaggregated budget data in Nepal to facilitate an active community of users that can access and utilize this information.

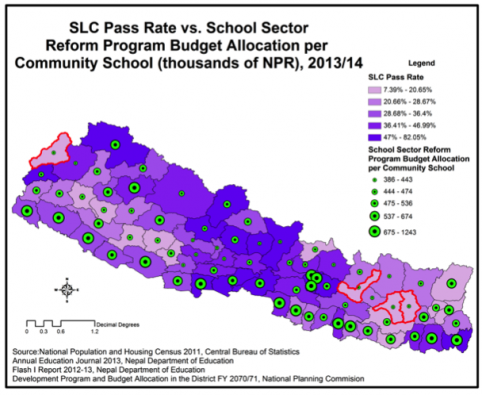

The Freedom Forum is mapping district, sector, and project-level information to help citizens more easily interpret how Nepal’s national budget is being allocated at the community level. Comparing district budget allocations with local development indicators, Freedom Forum’s data visualizations underscored disparities between government spending priorities and socioeconomic need. A map overlaying literacy rates with the allocation of funding for a School Sector Reform Project (pictured below) is one such example.

During the course of the Open Data Working Group event, civil society voices converged upon three points. First, for open data to succeed, the movement needs users and long-term commitments from government. Second, the future of open data lies in producing context-specific, micro-level data. Third, media and civil society organizations are needed as information intermediaries to bridge the gap between the supply-side and demand-side of open data. Cross-cutting all of these themes, participants emphasized the enormous opportunity for local level government to function as an important driver of development in Nepal’s emerging open data ecosystem.

The key takeaway: If the open data movement is to succeed in meeting its objectives, the next phase of Nepal’s open data revolution must be citizen-driven. In order to do this, we need to answer several questions. Who are the end users of open data and what kind of information is meaningful to their lives? What tools are needed to get the right data in the right hands? And how can we forge sustainable relationships and close the feedback loop between government actors, information intermediaries, and citizen beneficiaries on the ground?

Using geocoded data to map and analyze aid information and national budgets is the perfect starting point to explore some of these questions, and to better understand what open data signifies for citizens.