More than two weeks after a massive 7.8-magnitude earthquake hit the country and killed nearly 9,000 people in April of 2015, the first help to reach the highest village in Makalu region was a single man. Adrian Hayes, an Australian hiker, trekked in unsupported and on foot to some of Nepal’s most remote villages, using his medical training to assist villagers where he could and taking reports of damage and deaths back to aid agencies. For many villages, he was their first contact with the outside after the quake; some villagers told him they “did not expect to receive any help from their government for years.”

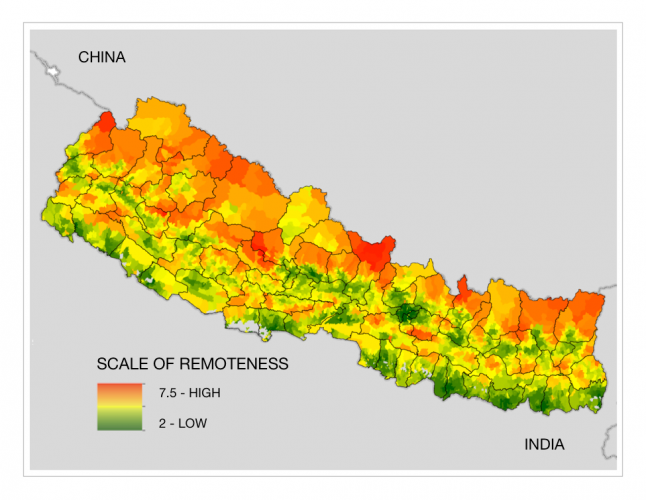

Figure 1. A scale of remoteness across Nepal

Understanding remoteness better will improve aid implementation and post-disaster recovery in Nepal. As a 2016 AidData Summer Fellow in Nepal, I used spatial data from the Government of Nepal and the USAID/Nepal Geospatial Lab to create an indicator of remoteness across Nepal that development agencies like USAID can use in the future to identify at-risk locations and populations based on accessibility and better target aid to them.

Numbers, not anecdotes

Remoteness is not homogeneous across the country. Various factors, including the existence of roads, road quality, methods of transportation available, and steepness of slope, all contribute to accessibility. The questions I sought to answer are: where are the most remote Village Development Committees (VDCs) of Nepal, and how much more remote are they than the average VDC? Furthermore, which groups of people — a caste, ethnicity, income level, gender — are the most affected by remoteness, and are they receiving aid proportionate to their needs?

Knowing precisely where the most remote locations are and who is most affected by remoteness makes it possible to analyze geographic variation in the economy, agriculture, healthcare, and education, and better target aid to areas that need it most. For vital post-disaster relief, aid implementation and planning, Nepal needs numbers, not just anecdotes, on remoteness.

You can't get there from here

Remoteness itself is an amorphous term. In this case, remoteness refers to the difficulty of access to goods and services and transportation. Specifically, it includes distance from roads, airports, and district headquarters; slope and elevation; land cover; and presence of rivers.

The methodology used is a simple weighted linear combination (WLC). Each factor (e.g., slope, rivers) was reclassified on a scale of 1-10, with 1 being not remote at all and 10 being extremely remote; given a weight based on its effect on remoteness; and combined with the other factors.

Inherent in the WLC is the linear reclassification of the variables. The difference between a rating of 1 and 2 is the same as the difference between 9 and 10. Without getting too far into the weeds, this approach has its limitations. For example, the steeper the slope, the more remote an area is — but an area above a certain grade of slope is plainly inaccessible, and no linear scale can reflect this appropriately. This was combatted by using non-linear scales whenever possible, and borrowing scales from similar methodology if it existed. Specifically for slope, the modified scale reflects the methodology of a team veteran from the Survey Department of the Ministry of Land Reform and Management: 0-12% slope ranked as 1, 12-24% ranked as 2, and so on until 48+% slope which is ranked as 10 and totally inaccessible.

The weights of factors in the final combination were determined in collaboration with USAID/Nepal’s GIS Specialist, Indra Sharan KC, and its head economist. Slope, distance from district headquarters, and distance from roads were deemed most important and collectively accounted for 70% of new scale for the resulting map.

The result of this reclassification, weighting and combining is an indicator of remoteness across Nepal. It is not an indicator of travel time, or of access to services like education or health. Averaged to the VDC level, this quantification can be compared to population density or used in a regression to evaluate the effect of remoteness on agriculture, health, demographics, or any area of interest.

This one imperfect indicator provides a platform to start observing spatial patterns, illustrate the demand for granular data, and manifest the evidence of remoteness beyond just our anecdotes. Ultimately, it will allow us to make more efficient and targeted choices with our aid.