The international community has taken important steps in recent years to expand the definition of development finance, but major gaps remain. One such gap is religiously-affiliated aid, particularly Islamic aid. Zakat, one of the basic practices of Islam (the third of the "five pillars" of Islam), is an important example of this gap. A practice observed by nearly a quarter of the world’s population, Zakat requires Muslims to donate roughly 2.5% of their disposable income to charity, specifically to the poor and needy and six other beneficiary groups listed in the Qur’an.

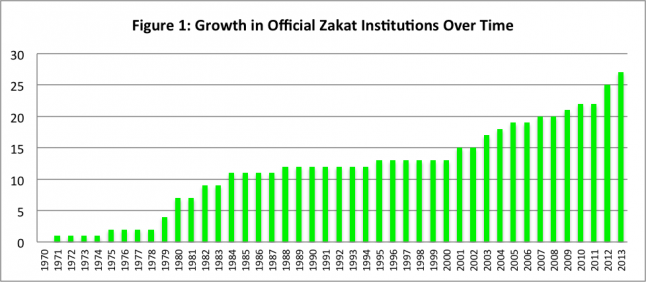

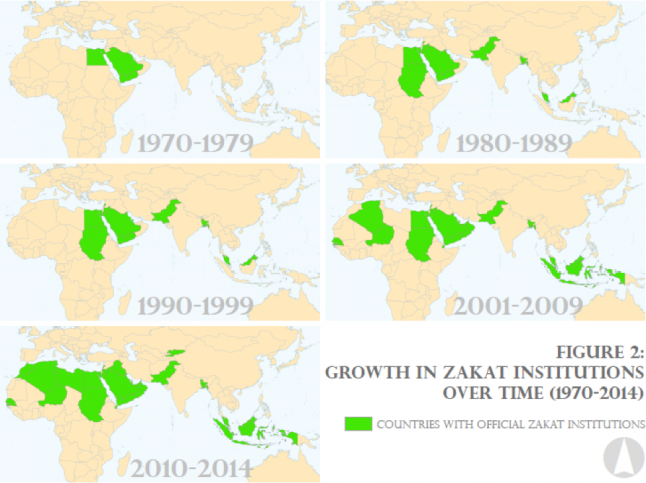

Zakat has become an increasingly institutionalized, transnational practice that focuses specifically on poverty alleviation. In the late 1980s, governments across the Islamic world began establishing official agencies to manage the collection and distribution of zakat. This trend accelerated again in the past 15 years (see Figures 1 and 2).

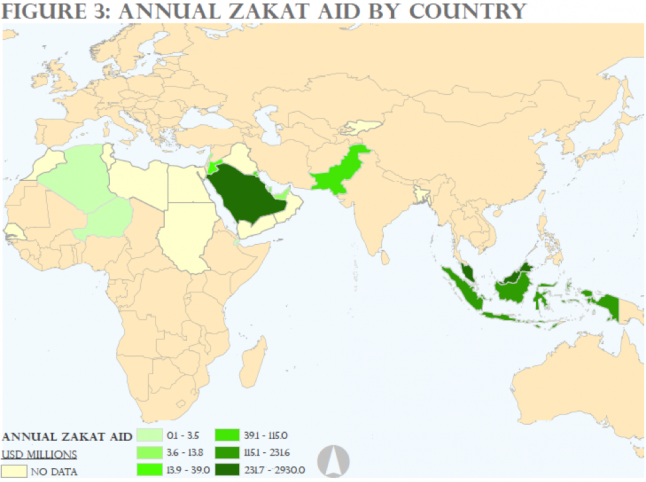

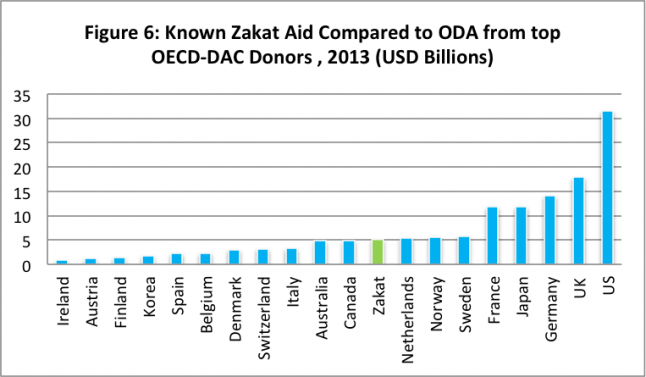

The limited data available suggests that zakat agencies manage billions of dollars of domestic and international aid each year (see Figures 3 to 5). Compared with OECD-DAC estimates of Official Development Assistance (ODA), official zakat institutions would rank among the top ten donors (see Figure 5). While official zakat is not the same as ODA, comparing the two types of financial flows gives an idea of the magnitude of official zakat and its role in development assistance. This comparison is particularly striking given the substantial amount of missing data on zakat. AidData has launched an effort to better understand the role of religious aid in ODA and measurements of development finance in the Arab world.

Source: OECD Query Wizard for International Development Statistics (QWIDS), 2014

Policymakers and academics outside the Muslim world tend to see zakat as entirely separate from development finance due to its religious nature. In doing so, they overlook the important role that zakat plays in social welfare and aid, increasing the potential for duplication of efforts where the activities of zakat institutions overlap with those of international development institutions.

Take USAID and the Palestinian Zakat Fund, for example. Using budget information from the Palestinian Zakat Fund and AidData’s data on USAID ODA in 2010, we find that the assistance from these two groups funds highly similar activities and targets the same segments of the population (see Figures 1 and 2).

Forty-eight percent of USAID’s assistance goes towards “Social Services”. AidData’s project descriptions show that this aid consisted of two kinds of activities – cash or in-kind transfers to the poor and aid to assist vulnerable populations – the disabled, orphans, the elderly, female heads of households, etc. Similarly, “Support to Orphans” and “Aid to Families” account for 73% of Palestine Zakat Fund assistance, and also involve regular cash and in-kind transfers to orphans, female-headed households, and low-income households, especially those with disabled and elderly members. There is overlap to a lesser degree in the areas of health and education.

With a budget of roughly 23 million USD for the West Bank alone in 2011, the Zakat Fund provided twice as much aid as UN agencies to the West Bank and Gaza in 2011. Although this data represents only a sliver of zakat activity, the activities of zakat institutions are fairly similar across countries.

It is clear from this analysis that zakat institutions play an important role in development and social welfare. Failing to consider zakat in broader conversations about development finance could result in missed opportunities for aid coordination and duplication of efforts.

As the development community seeks to embrace broader, more inclusive partnerships and develop more comprehensive measures of official development finance, zakat is an important field to consider. Development agencies should seek to better understanding the role of zakat within the framework of development finance. Together, zakat institutions and development agencies should initiate a dialogue on the potential for mutually-beneficial information-sharing and coordination. There will undoubtedly be challenges: religious principles encourage discretion around zakat donations and distribution, and separation from budgets of secular institutions. However, zakat institutions are increasingly emphasizing transparency – particularly in the face of anti-terrorist financing regulations – and have demonstrated an interest in dialogue. For these reasons, it is an important time for zakat to enter the discussion around development finance.

For more information on zakat institutions: Algeria (1, 2, 3) , Bahrain , Bangladesh (1, 2) , Brunei , Djibouti (1, 2) , Egypt , Gambia , Indonesia (1, 2) , Iraq (1, 2, 3) , Jordan , Kuwait , Kyrgyzstan (1, 2) , Lebanon , Libya , Malaysia , Maldives, Morocco, Niger , Oman , Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar , Saudi Arabia , Senegal , Sudan , Tunisia , United Arab Emirates , Yemen