As USAID’s Alex Dehgan would tell you, it took 20 years to grow Africa's cell phone user base to 100 million, but only 3 years to reach 300 million. Today, 700 million Africans use cell phones, often with SMS texting capabilities. Development practitioners and private enterprises alike are attempting to leverage this greater connectivity through crowdsourcing initiatives, which call upon citizens to provide input to improve a wide variety of programs. In this post, I look at what we can learn from student entrepreneurs and randomized control trials in Africa to get the incentives right for citizens to participate in such feedback mechanisms.

Young African students studying at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda are among those seeking to engage citizens in solving pervasive development challenges. I learned of two noteworthy student projects harnessing open data and SMS to magnify the voice of local communities, Kudu and FindIt!, at a Resilient Africa Network event in June.

Kudu enables sellers and buyers of agricultural products to easily share information via SMS using a student-designed interface. Farmers advertise crops they want to sell at what price and are matched with buyers interested in purchasing their products. Since 2012, Kudu has attracted over 1,000 users and is remedying traditional information asymmetries by helping buyers and sellers easily find each other and to minimize time and cost.

FindIt! recognized that students were spending time and money traveling to their university to access critical information on exam times, assignment due dates, and campus events only available on classroom chalkboards. FindIt! inventors, Robert Sebunya and Daniel Olel, encourage students to subscribe to SMS blasts for self-selected interest areas and plan to expand operations beyond Makerere students in future.

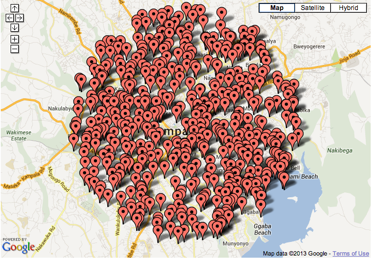

Development practitioners also believe crowdsourcing could help close the development feedback loop by asking the intended beneficiaries of aid to submit feedback via SMS. This process could help improve foreign aid accountability and allow local citizens to access and utilize development data. There is a critical difference between the crowdsourcing initiatives implemented by Makerere University students and efforts to use crowdsourcing to close the foreign aid feedback loop, however. Citizens may not reap immediate benefits from submitting real-time feedback about foreign aid projects. Instead, the benefits of giving feedback may only accrue to citizens and their communities over time. This summer, I worked with researchers from the Political Economy Development Lab at Brigham Young University and AidData to break ground on a multi-year study assessing whether crowd-sourced feedback can improve garbage collection in Uganda. Kampala, like many cities in developing countries, suffers from unreliable public service provision. Solid waste removal is no exception—only an estimated 40 percent of trash is removed through the formal waste removal system. Private contractors perform much of the removal, but they are subject to corruption and a lack of oversight. Building upon earlier research about how to recruit citizen monitors, my colleagues and I randomly assigned 480 out of 1,000 specific areas of Kampala to receive citizen monitoring, assigning an individual in each zone to report on solid waste removal in her neighborhood. For each area, we administered a baseline survey to 10 households where we asked them about solid waste removal in their neighborhoods. We ultimately seek to measure changes in solid waste removal as a result of their feedback.

Once the multi-year study has been completed, we will return to these households and ask whether the quality of their solid waste removal service has changed. In this way, we can measure if solid waste removal indeed improved as a result of citizen monitoring.

What can we learn from crowdsourcing initiatives implemented by student entrepreneurs or researchers conducting randomized control trials? It is my hope that with each new initiative, we are able to better understand how to engage citizens and solicit their feedback. From these experiences we can identify crowdsourcing best practices which can be shared and utilized in a variety of applications, including making foreign aid more effective.