Across large swaths of the developing world, a new trend is taking hold: governments are targeting public and private investments in specific geographic areas in the hopes of creating spatial “development corridors.” These strategies are guided by the belief that concentrating and co-locating infrastructure investments in specific locations can create clusters of interconnected firms, nurture the development of value chains, reduce unemployment, and improve the provision of basic public services.

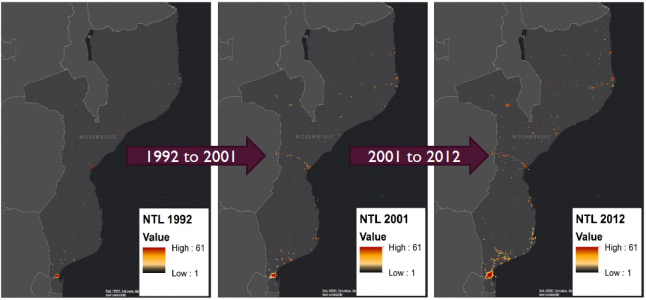

By way of illustration, consider Mozambique. Since the late 1990s, its government has made a series of coordinated infrastructure investments to establish a development corridor between the country’s central provinces near eastern Zimbabwe and the seaside port of Beira. With high-resolution satellite measurements of nighttime light, one can visually track the creation and growth of this development corridor over time. In Figure 1, it is easily observable: it is the horizontal, orange-and-red “line” that bisects the middle of the country, bending southeast to the coast.

Figure 1: The Development of the “Beira Corridor” in Mozambique

Some cash-strapped governments in resource-rich countries are going a step further, demanding that incoming foreign investors build and maintain local infrastructure in exchange for contractual rights to extract and export natural and nonrenewable resources like timber, rubber, oil, gold, and iron ore.

Liberia is a case in point. Its devastating, fifteen-year civil war finally ended in August 2003. The Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf administration, which came into power in 2006 through a free and fair election, has made foreign direct investment (FDI) the centerpiece of its growth and development strategy. However, unlike previous administrations that adopted a laissez-faire approach, it has required that private investors build and rehabilitate roads, ports, bridges, power plants, and health and education systems in and around the communities where their investments are physically sited.

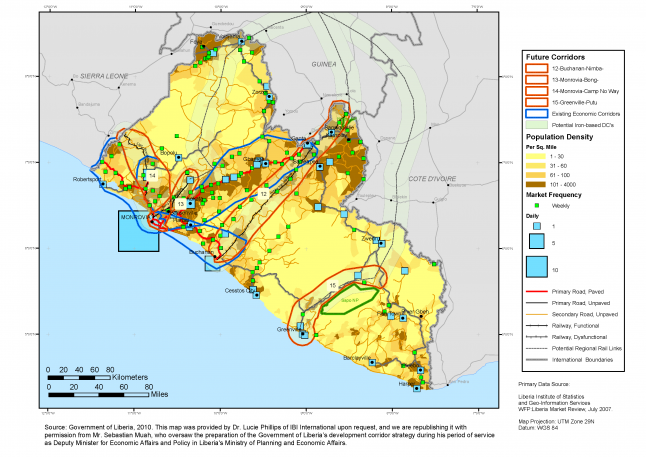

The Government of Liberia has also prioritized the creation of three new development corridors near population centers and existing markets (see Figure 2). (A fourth potential corridor that could run north from Monrovia to the Wologizi deposit was identified; however, given that the deposit had “not yet been proven economically viable,” it was not assigned a high level of priority. For more information, see: Government of Liberia. 2010. Liberia’s Vision for Accelerating Economic Growth: A Development Corridor Desk Study. Monrovia, Liberia: Ministry of Planning and Economic Affairs). The Government of Liberia's goal in developing these corridors has been to maximize the economic multiplier effects that can be generated by infrastructure financed and supplied by mining concessionaires.

Figure 2: The Johnson-Sirleaf Administration’s Development Corridor Priorities

But has this strategy actually worked? We recently completed a geospatial impact evaluation that rigorously estimates the impact of natural resource concessions in Liberia on local economic growth outcomes, in the years since the Johnson-Sirleaf administration assumed power.

Here’s what we found:

- The evidence suggests that natural resource concessions improve local economic growth. On average, natural resource concessions increase nighttime light by 0.58% in the 25 km surrounding concession areas, which roughly corresponds to a 0.17% increase in local GDP.

- Mining concessions have a positive effect on local economic growth. By contrast, there is no robust evidence that agricultural concessions register consistent effects on economic outcomes.

- U.S. concessions do not have a discernible effect on local economic growth, but Chinese concessions do. In particular, Chinese mining investments seem to have a particularly large impact. We recovered evidence that that they increase nighttime light output by 1.26% in the 20 km surrounding their concession areas, which is roughly equivalent to a 0.38% increase in local GDP.

These results suggest that the Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf administration’s FDI-led development corridor strategy is working. Note that concessions subject to more demanding public good provision requirements (e.g. mining investment projects) produced higher levels of economic growth than those that faced less demanding public good provision requirements (e.g. agricultural investment projects). Also, investors that were more readily able to satisfy the government’s public good requirements (e.g. Chinese concessionaires) achieved larger economic growth impacts than investors that were not as well-positioned to meet such requirements (U.S. concessionaires).

Going forward, we hope to evaluate whether and how natural resources concessions impact non-economic outcomes, such as social protest, land conflict, violence, and deforestation. The growing availability of subnational geo-referenced investment, outcome, and covariate data has put this type of analysis well within reach.