Members of the Uganda Economics Association debate Uganda’s record-high 2015/2016 budget, whose main focus is investment in the infrastructure sector.

On a recent trip to Uganda’s Murchison Falls National Park, located some 260km outside of the capital city of Kampala, I passed over the enormous Karuma hydroelectric power plant, currently being constructed by a Chinese state-owned construction firm. Later in my travels, I came across a highway under construction, also being built by a Chinese firm. As these two examples clearly suggest, China is playing an important role in financing Uganda’s rapid rate of infrastructure construction.

Infrastructure constraints are arguably Uganda’s largest current impediment to economic growth, with Uganda’s economic and political leadership prioritizing infrastructure investment over all other sectors. Recent reports calculate that the limited nature of Uganda’s infrastructure constitutes around 58% of the productivity constraints faced by Ugandan industries. This accounts for much more than lack of finances, red tape, and poor governance combined. Additionally, the World Bank calculated that if Uganda’s infrastructure was as good as that of the island nation of Mauritius, which has the best infrastructure in Africa, growth could increase by as much as 3.8 percentage points annually.

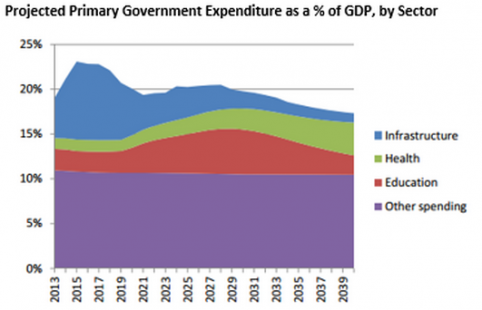

Uganda’s investment in infrastructure is experiencing a monumental surge. (Ministry of Finance, Planning, and Economic Development of Uganda)

Uganda is currently investing in huge infrastructure projects in order to further enable industrial and economic development. The country is looking to China to supply more than $10 billion in funding for the construction of many of these projects, including a new railroad network, roads, and several hydroelectric power plants.

Of the hydroelectric power plants currently planned or under construction throughout Uganda, most are being constructed by Chinese construction firms and funded by loans from China at semi-concessional rates. The Karuma and Ayago power stations, each with a capacity of 600 MW, will become the two largest power plants in the country upon their completion. The cost of each of these projects is around $2 billion US, and will more than double Uganda’s power generation capabilities.

In a March 2013 blog post, AidData-affiliated researchers reported their findings that Ugandan citizens demonstrated a preference for American aid over Chinese. This preference evidently does not extend to policymakers, as Chinese state-owned firms have dominated transport and power sector contracts.

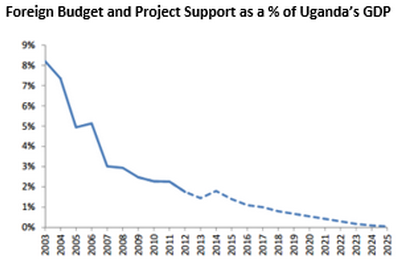

This revealed preference for Chinese-funded infrastructure projects may suggest that China’s approach, which is not as concerned with human rights performance or may be better aligned with the goals of Uganda’s political elites. China’s model, crucially for Uganda, is not dependent upon human rights performance or lack of corruption. In the past four years, western humanitarian and development aid has repeatedly been suspended because of corruption (in the case of the United Kingdom) on the part of Ugandan officials and because of the passing of anti-homosexuality legislation (in the cases of Norway and Sweden). Far from resulting in policy changes, Ugandan officials responded that “the West can keep their ‘aid’... we shall develop without it.”

Uganda looks to China to fund its infrastructure projects because China’s state-owned companies will accept future payments, from Uganda’s projected oil revenues, while Western contractors expect up-front payment. Uganda’s long-time president, Yoweri Museveni, further explained their growing East-looking orientation because China offers cheaper capital, does not meddle in domestic issues, and comes with “big money.” Criticizing the World Bank’s use of conditionalities, Museveni said, “how can you have structural adjustment without electricity? The Chinese understand the basics.”

Western aid agencies aren’t providing the “big money” President Museveni is looking for. (Uganda’s Ministry of Finance, Planning, and Economic Development)

These trends challenge many of the assumptions upon which Western aid is based. If there is an alternative to Western aid, will conditionalities simply push low and middle income countries to look to China? It additionally demonstrates that Chinese aid may be better suited to provide the support that Uganda is looking for in this stage of its development. What will this mean for Western soft power in Uganda, and in East Africa in general? The question remains to be answered.

Several weeks ago, a Ugandan driver was taking me back to my apartment. As we approached my neighborhood, he mentioned that he had lived in the same neighborhood twenty years ago. We bumped along the rust-colored dirt streets, carefully dodging potholes and rocks, and he observed, “All of the buildings here are new, but the roads, they are the same.” If, in twenty more years these same roads are paved, you can bet it will be because of Chinese aid.