Once on the receiving end of aid, Brazil is now actively positioning itself to share lessons learned in growing its economy with other countries. In recent years, Brazil has rapidly increased its outgoing aid dollars to Haiti, Portuguese-speaking countries in Africa, the United Nations Development Program, and the World Food Program. Brazil’s effective management of large-scale social programs, such as Bolsa Familia and progressive agriculture, has prompted other countries to seek out its technical expertise. To keep up with this demand, the Brazilian Cooperation Agency (ABC), the government's agency for technical cooperation, tripled its budget in the 2000s.

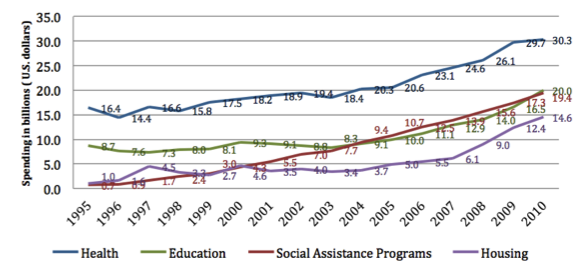

Social Program Expenditures by the Brazilian Government in billions of dollars(per sector) (1995-2010)

Brazil’s expanding focus on development abroad corresponds with its broader efforts to assert its global role. But the government’s international aspirations have provoked a backlash from some of its constituents. Brazil’s hosting of the 2014 FIFA World Cup this summer is a case in point, as protestors used the spotlight to illuminate Brazil’s domestic failures and argue against excessive spending on the World Cup, particularly billions spent on the construction of 12 world-class stadiums.

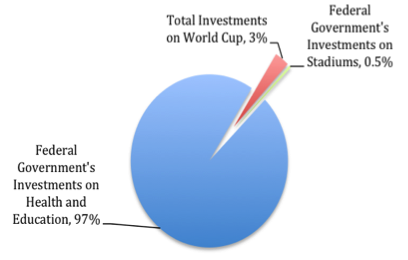

Digging into the numbers, however, shows a more complicated picture. As Diego Von Vacano and Thiago Silva explain, Brazil’s World Cup spending – divided among federal, state and municipal governments – amounts to about $11.2 billion, a mere 3% of Brazil’s total social spending over the same period of time. Of the remaining 97%, $363 billion is directed towards the health and education sectors. Brazil’s investments in expensive, impractical, sports infrastructure certainly do raise questions of priorities, especially when problems of political corruption, poverty, and economic inequality persist. But it is also worth noting that the World Cup investments are a small fraction of government expenditures on its social programs.

Expenditures on the World Cup compared to investments by the Federal Governmenton Health and Education (2010-2014)

But let us circle back to Brazil’s role in international aid. What, if anything, have we seen in Brazil’s approach to the World Cup that could have implications for its development spending? Brazil has the seventh highest GDP in the world. How it chooses to spend its money matters, especially as South-South cooperation becomes more and more important in the development landscape.

If Brazil approaches its role as a donor in the same way it has undertaken its role as World Cup host, we will likely see a ramping up of its assistance efforts abroad. As Brazil and other emerging donors who do not report to the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee provide a growing share of development finance, capturing what and where these donors are funding is increasingly important. In the case of Brazil, specifically, the government has been criticized for being weak in data management, monitoring and evaluation, and institutional autonomy.

Even with the World Cup over, Brazil will have no shortage of attention as a sponsor of international sporting events as it prepares to host the Summer Olympics in 2016. But more attention and greater transparency is needed with regard to Brazil’s other global role as an emerging donor.