In February 2007, I went to a conference on Liberia, organised by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Washington, DC. President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf presented her government’s plan to rebuild the country after a devastating civil war. The next person to speak was the Managing Director of the IMF, Rodrigo Rato. He announced that IMF staff had reviewed the government’s economic policies, and the Fund had decided to lift a declaration of "non-cooperation" that had been in place since the start of the Liberian civil war in 1990. This would be the first step to cancelling Liberia’s crippling foreign debt. A round of applause went through the room.

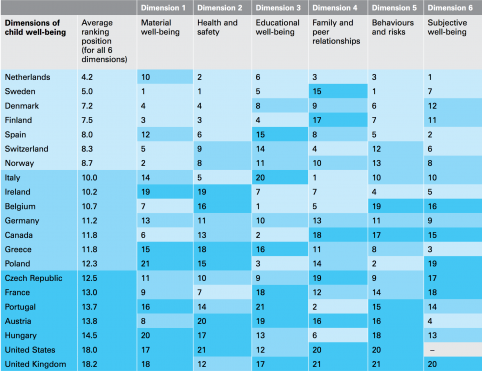

Scorecard of Child Well-Being in Industrialized Countries (Source: UNICEF 2007)

On the same day that I was in Washington, the UN Children’s Fund, UNICEF, published a report which compares child well being in 21 rich countries. They found that the UK, my home country, was the worst rich country in which to be a child. The report received some attention in the UK, as the Labour government had made fighting child poverty a priority. George Osbourne, a leading opposition politician, accused the government of "failing this generation of children." But a year later the financial crisis struck, and fighting child poverty dropped off the agenda. By 2013, George Osbourne, by now the Chancellor, was defending his own austerity policies against renewed criticism from UNICEF. On May 7th, his government was re-elected with a mandate to cut welfare payments further.

Why did the IMF’s assessment of Liberia’s economic policy have lasting consequences, while UNICEF’s assessment of UK child poverty did not? Two obvious answers are power and money. The UK is a permanent member of the UN Security Council, while Liberia is a small, aid-dependent country. An IMF staff review can unlock billions of dollars in loans or debt cancellation; no UN report can do such a thing. Beyond those answers, though, we know very little of how external assessments influence governments.

This is where a new report from AidData, "The Marketplace of Ideas for Policy Change," comes in. The report compares the impact of over 100 external assessments on what governments do. They range from IMF staff reviews to cross-country comparison tables with a focus on developing countries. Some findings support the "money and power" thesis: external assessments typically have more influence over policy priorities than actual policy design and are most influential in countries that are small, heavily aid-dependent (mostly in Africa) or trying to join the European Union (mostly in south-east Europe). Other findings were more surprising:

- Assessments have more influence if they focus on the "nuts and bolts of government. This may explain why the World Bank’s "Doing Business" reports are so popular: they give governments a checklist of things to fix

- Countries with a free press and democratically elected leaders pay more attention to external assessments, maybe because these get picked up in the press and contribute to domestic political debate

- Governments want more specific and actionable advice on how to improve their performance. For instance, the IMF agreed a clear set of steps with Liberia to give the government debt relief. The US Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) uses a public scorecard with 20 indicators to determine eligibility for assistance, but since governments can’t influence all of these indicators directly, the MCC’s eligibility process motivates fewer reforms than it otherwise could.

- On a related note, nobody seems to like governance assessments. The authors suggest that may be because fighting corruption is hard and threatens vested interests. I would also suggest that you can get headlines by proclaiming "zero tolerance" on corruption, but it takes years to see meaningful results and even then it may not change the perception of your country in the outside world

Two big things were missing from the report for me. One, I didn’t see any analysis on the long-run impact of these assessments on development outcomes. The authors noted that Rwanda and Ethiopia pay less attention to them than many of their neighbours do, but have impressive rates of growth and poverty reduction. I would also like to know which assessments influence developed country governments. Here at Publish What You Fund, we would love to know how to make our Aid Transparency Index more effective.

My conclusion: money and power still matter, but simplicity does too. If you are trying to get the attention of a developing country government, tell them clearly what the problem is and what they can do to fix it, starting on Monday morning. You’ll get more attention, help them make the case, and the reform is probably more likely to work too.