Does “ground game” — the strength of a development partner’s local presence and direct engagement with recipient government officials — affect how in-country decision makers assess the performance of development partners? AidData’s Listening to Leaders report provides a snapshot of the “ground game” of development partners, as reported by participants in its survey of nearly 6,750 policymakers and stakeholders in 126 low- and middle-income countries.

The evidence on the impact of “ground game” is mixed. Amadou Diallo and Dennis Thuillier, two researchers from the University of Montreal, find that frequent engagement between development partners and their in-country counterparts is very important for building sufficient trust to successfully implement projects and programs of mutual interest. On the other hand, two World Bank researchers, Stephen Knack and Aminur Rahman, conclude that constant engagement could result in a negative outcome, by distracting host government officials from pursuing development projects or reform programs that align with national priorities in favor of satisfying the demands of donors.

Listening to Leaders examines the relationship between a development partner’s frequency of communication and its perceived influence in the development process. The results shed light on whether and how much “ground game” really matters.

3,400 recipient country government officials were surveyed on the frequency of their communication with development partners over the period 2004-2013, and rated the performance of those partners on a range of criteria.

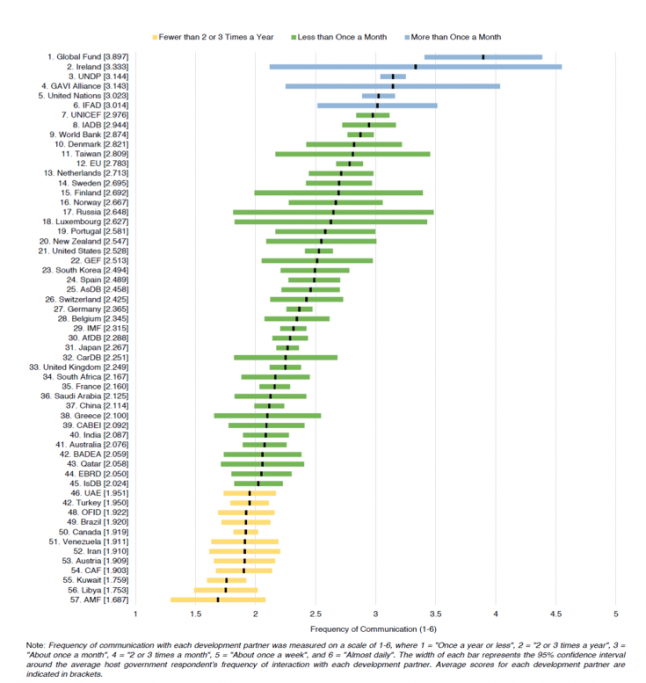

The report finds that multilaterals and smaller partners with a specific sector focus — such as the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) and The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria — are the most communicative partners, interacting with host government officials more than once a month. After this group are the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) bilaterals with a communication frequency of less than once a month. In third place are non-DAC donors — countries such as China and Kuwait that are not part of the OECD DAC — many of which do not publish information about their aid disbursements.

Figure 1: How Often Did Development Partners Communicate with Host Government Officials?

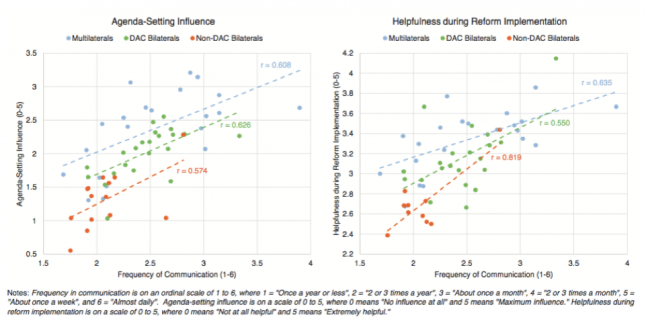

In addition to frequency of communication, the survey asked participants to rate the performance of development partners across three dimensions: (1) usefulness of policy advice, (2) agenda-setting influence, and (3) helpfulness in policy reform implementation. The report then analyzes the relationship between a development partner’s performance across these three dimensions and its frequency of communication with in-country decision makers.

The results (Fig. 2, below) indicate that frequent communication is indeed associated with improved perceptions of a development partner’s agenda-setting influence and helpfulness during reform implementation. However, the authors do not find a strong association between frequency of communication and an improved perception of the usefulness of a development partner’s policy advice.

Figure 2: Frequent Communication Is Associated with Improved Perceptions of Development Partner Performance

Overall, the report finds that most high-performing development partners usually have a strong ground game. Interacting and engaging with host government officials may help development partners reap policy influence dividends, but the relationship between a development partner’s frequency of communication and its perceived performance is not yet entirely clear.

It may be that frequent communicators get “a seat at the table” when decisions are being made about reform priorities, and are the first to be asked for help by host government officials seeking to translate ideas into action. However, a high frequency of communication does not necessarily mean that a development partner’s advice is perceived to be more useful; while the quantity of communication matters, the form it takes and the salience of that communication is likely just as important. These findings make a strong case for further research to investigate whether or how the salience or quality of communication affects host government perceptions of a development partner’s level of agenda-setting influence, helpfulness in implementing reforms, and usefulness of policy advice.

Within the development space, there is currently a broad debate over whether development organizations do better to specialize and focus on a narrow set of countries and sectors, or go broad and maximize their reach and visibility to hit a wider variety of targets. Both strategies have merits, but the latter approach is not as conducive to increasing communication and engagement with in-country counterparts. Making breakthroughs with in-country counterparts may require development agencies to take a more circumscribed (i.e. smaller) and focused role that involves frequent, direct communication. For development partners who specifically want to shape policy through setting the agenda for reforms, there’s an argument to be made for a smaller, not larger, footprint.