Last week, an ISIS-supported suicide bomber killed eight people when his car exploded outside of the presidential palace in Aden, Yemen. This is just one of countless attacks that have been carried out by the Islamic State and Al Qaeda in Yemen since the 2011 launch of the Yemeni revolution.

In January of that year, Yemenis took to the street to demand the resignation of President Ali Abdullah Saleh. Rather than step down, the Saleh administration met protestors with a show of force. The first of many acts of government-sponsored violence, on March 29, 2011, Yemeni forces stormed into Taizz’s Freedom Square, “shot protestors with assault rifles,” and “set fire to protesters’ tents.” After a long fight, President Saleh eventually relinquished power in February 2012, setting off a period of violence and instability that continues today.

The Yemeni Revolution was not entirely unexpected, but rather the culmination of years of widespread political disenfranchisement. Under President Saleh, Yemen’s decision-making was dominated by the influence of a powerful “inner circle” of family, Sheikhs, and military commanders. Without widespread pressure for reform, President Saleh was unable to overcome the opposition of this inner circle—itself reliant on the status quo—and undertake the reforms needed to improve investment and boost growth.

It was in this constrained context that the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) struggled to operate. After several stalled attempts to reduce corruption, extend political rights, and strengthen the rule of law in Yemen, the MCC made some headway in 2006. In an effort to regain Yemen’s eligibility for an MCC Threshold Program, President Saleh capitulated to the MCC’s requests. He reshuffled his cabinet, passed anti-corruption legislation, removed several corrupt judges, and eliminated payments to “ghost workers.” However, the MCC’s success in Yemen did not last. Without broad and sustained support for reform, Saleh failed to surmount the entrenched interests of Yemen’s inner circle, and the reform package stalled.

The Yemeni example demonstrates how the political environment can constrain the ability of governments and development organizations to advance meaningful reform. A lack of broad domestic support for reform, even in the presence of a conciliatory chief executive, not only delayed the adoption of the reforms desired by the MCC, but also undercut their momentum once implemented.

In Listening to Leaders, we identified the breadth of support for reform among domestic governmental and non-governmental actors as one of the primary drivers of development partner influence. We found that strategic alliance with a few members of executive branch is not likely to have much impact on the ability of a development agency to catalyze reform. Instead, donors should generate public pressure for reform among multiple domestic political actors, such as trade unions, business associations, political party leaders, the military, and civil society organizations.

Why, then, do many development partner organizations continue to focus their efforts on fostering partnerships with a handful of officials in the executive branch? The Yemeni example provides one possible explanation: with limited budgets, short timetables, and a position on the outside of domestic politics, donors often have no choice.

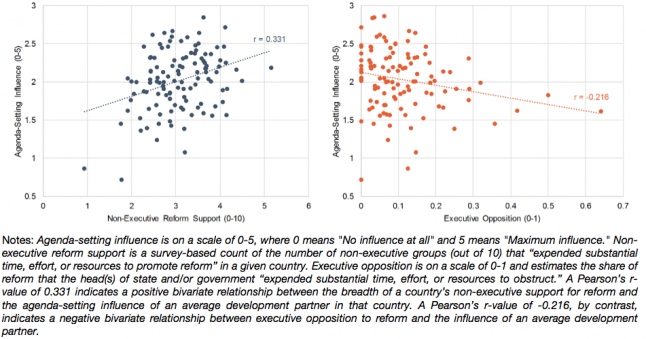

Fig 1. The Countervailing Effects of Broad Domestic Support and Narrow Executive Opposition

As highlighted in the right side panel of Figure 1, the opposition of just one veto-wielding government executive can undermine a development partner’s ability to secure the adoption of even the most widely supported reform effort. Any foreign or international agency that chooses to invest its limited resources in the costly endeavor of securing widespread support for reform must tread carefully. Even in a country with a decidedly pro-reform citizenry, if the policy changes that a donor proposes run counter to the interests of the Head of State, that donor is not likely to influence the reform agenda.

In Yemen, a country characterized by a strong “inner circle” and otherwise widespread political disenfranchisement, the MCC was unlikely to build an effective base of reform support outside of the Office of the President without an ambitious and costly outreach campaign. So it instead concentrated its efforts on winning the support, however tepid, of Yemen’s Head of State, whose opposition might have otherwise prevented the adoption of the MCC’s preferred policy changes.

Our study highlights the fine balance that development partner organizations such as the MCC must strike in order to effectively promote meaningful reform. While earning the support of executive leadership is critical, it is equally (if not more) important for development agencies to build broad support for reform among the electorate. The latter approach has few immediate payoffs, but is critical to the long-term viability of the reform process.

One possible way to achieve this is to work closely with local organizations to prioritize reforms that they advocate. Another could be to allocate aid in a way that aligns the incentives of government with the priorities and needs of citizens. Meanwhile, communication with government leadership can continue to foster goodwill and reduce the likelihood of executive opposition. To walk this fine line is by no means easy; however, it would serve development stakeholders well to perfect the balance if they want to promote sustainable reform that is focused beyond the needs of a select few.