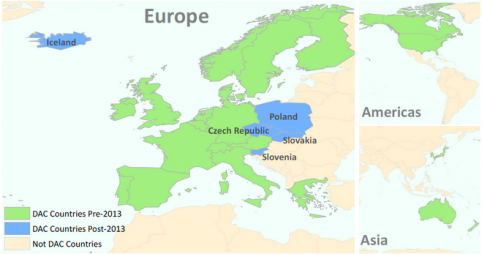

Four Central and Eastern European countries joined the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) last year. The ascension of the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovenia and the Slovak Republic to the DAC signals a broader trend underscored by OECD Director Jon Lomoy at the time, “the global development landscape is changing fast and the OECD... is changing with it.” But as we look back one year on, has the DAC truly changed?

The Changing Face of the OECD DAC?

As discussed in previous blogs, development cooperation providers, modalities, and philosophies are increasingly diverse. Countries outside of the OECD-DAC -- non-DAC donors -- often understand and do development differently than OECD-DAC members. While Lomoy and other OECD leaders are very much aware of the growing role of these new development cooperation providers, some observers have asked whether the OECD-DAC’s conception of official development assistance (ODA) is still relevant.

Through opening the door to include Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries as full members, the OECD-DAC appears to be signaling its desire to keep up with new trends in development cooperation. But what does the inclusion of CEE countries in the OECD-DAC actually mean in practice?

CEE countries challenge simple dichotomies in conventional development assistance such as classifications between developing and developed, donor and recipient. Over the past decade, many CEE countries have become members of the European Union and attained high-income status. Yet, until recently, a large number of CEE countries were also considered to be “in transition,” seen primarily as recipients of official aid.

Despite joining the OECD-DAC and reporting their aid in line with ODA standards, CEE countries continue to feel some dissonance between the OECD-DAC narrative of development assistance and their own development realities. Scholars Lightfoot and Szent-Iványi have noted three points of divergence:

- CEE countries prefer to link aid to exports through tied aid and export support.

- CEE countries tend to concentrate aid among their regional partners, rather than targeting Least Developed Countries

- CEE countries tend to prefer focusing on areas where they can provide specific technical expertise in transition experiences

Are these gaps between how CEE countries and OECD-DAC understanding aid a failure of “socialization” on the part of the EU and DAC? From the perspective of Lightfoot and Szent-Ivanyi, the answer is yes. They warn that such a lack of consensus regarding development policy “fatally weakens” the unity of such organizations.

However, these issues also resemble common principles of South-South Cooperation (SSC) discussed in previous blogs. It is important to note that these CEE countries, by joining the DAC, have chosen a strategy much different than that of prominent SSC donors. Still, similarities between the aid preferences of CEE countries and SSC principles are evident. The preference of CEE countries for tied aid reflects the basic assumption that SSC should be mutually-beneficial. The focus of CEE countries on transition experiences reflects the respect SSC providers afford to the unique expertise of Southern countries, which is often best represented through technical cooperation. Similarly, the emphasis of CEE countries on regional partners is also in common with SSC providers and is linked to the idea of cooperation around shared development experiences.

Some of these patterns may present issues, such as the effect of export support on debt sustainability, to be addressed in an upcoming blog in this series. However, they are also part of the much larger, important aid philosophies and trends linked to SSC. In this way, these aid tendencies cannot easily be ‘socialized’ out of CEE countries. Perhaps, they should not be.

If the OECD-DAC’s inclusion of CEE countries is intended to signal the club’s ability to adapt in the face of a changing development landscape, longer-term DAC members should not ignore the different views on development assistance that new members bring, nor try to force its new members to conform to old definitions.

One year on, it is unclear whether the OECD-DAC is truly changing with the times or not. However, the OECD-DAC’s upcoming discussions around reforming the definition of ODA have considerable potential, particularly if they fully engage CEE members and other non-DAC countries.