It’s easy to get swept up in the hype around the ‘liberation’ of donor and government information fuelled by the open data movement, but ensuring that these data are used by citizens, policymakers and funders is easier said than done. Several basic conditions need to be in place to ensure that data are actually put to good use.

First, data at the project- and activity- level must be publicly accessible in a format that people can understand, use and compare. The majority of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) donors have begun publishing to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) registry, which provides for a common reporting standard across agencies. That said, the pace and quality of the reporting remain a work in progress, often preventing the data from being usable to greatest effect.

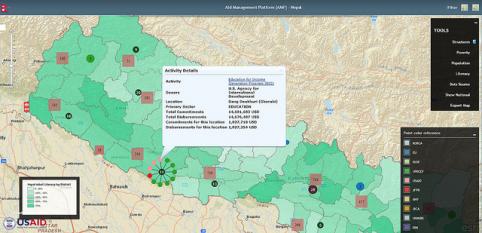

Second, donors and governments must systematically tag projects and activities with geographic information and make these data public. At AidData, we work with governments around the world to generate geospatial data and convert it into insights. In Nepal, for instance, the Ministry of Finance had implemented the Aid Management Platform in partnership with Development Gateway to track aid projects reported by over 40 donors, but recognized that more granular information was needed to better target domestic and external resources.

Nepal AMP: USAID Education Project location with Literacy Layer

In collaboration with USAID’s Higher Education Solutions Network and Nepal Mission, AidData and Ministry staff collected location information on over 21,000 project sites, representing $6 billion in donor commitments. The Ministry pledged to make and keep the data open to enable broad access by a host of users. Madhu Kumar Marasini, International Economic Cooperation and Coordination Division Chief and Joint Finance Secretary, remarked that “this openness will not only strengthen accountability in foreign aid mobilisation, but also provide additional opportunities to make aid more effective.” At the same time, donors like the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the Asian Development Bank have embedded geocoding into their internal processes and are now publishing this geocoded data to IATI.

Third, citizens, public officials and scholars must have mapping tools to visualize and make sense of the data. In Nepal, AidData and Esri, a company that supplies geographic information system software, integrated a mapping feature into the existing government Aid Management Platform, enabling a broad user base to explore the data.

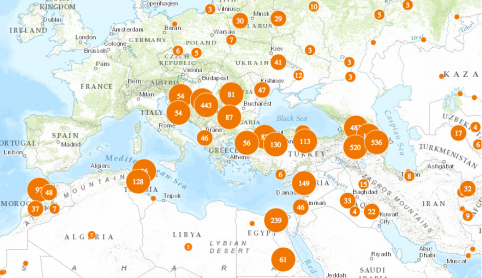

AidData.org Data Dashboard

Appealing to a global audience, AidData launched the AidData.org platform to lower the barriers to data exploration with easy-to-use tools to explore research questions, create maps and visualisations, Flashy tools and technology bring data to life, but building the capacity for more people to make meaning from it, from the civil society group in a remote village to a policy-maker in the capital city of a developing country, is critical and often overlooked. As such, sparking uptake and sustained use of data is the final frontier of the data revolution. From Open Data Bootcamps hosted by the World Bank, to hackathons in tech hubs around the world, there is a growing focus on building data literacy. Infomediaries and data journalists have the potential to reach more people by transforming raw data into stories, visualisations and analysis.

One innovative model that holds promise is Code4Kenya, which embeds tech-savvy fellows and developers in media and civil society organisations, with promising early wins, like the ‘Find My School’ application for comparing primary school performance. We need to seed more creative, grassroots approaches like Code4Kenya to make data relevant and useful to local organisations and citizens.

Spurring and sustaining demand for broad data use will not be an easy process. Citizens and communities need to experience first-hand how data can help them engage in dialogue about priorities and further their own development agendas. If information is to be relevant it needs to be closer to the lives, needs and aspirations of citizens. This is where more granular, local information is a foundational piece to the success of the data revolution.

As donors and governments invest heavily in the ‘supply side’ by opening up and creating vast stores of new data, devoting equal attention to kindling sustained demand and capacity for use of these data will be crucial.