There is growing evidence that in many developing countries a substantial percentage of public funding for sectors such as health, education, and infrastructure never reaches the intended beneficiaries. Some reports suggest that less than a quarter of funding is received. One group of researchers from the World Bank found that during the mid-1990s only 22% of public funding for school supplies actually reached Ugandan schools. More recently, the Indian government admitted that only 15% of its funding for employment programs reaches the intended beneficiaries. Estimates of "leakage" -- and methods for calculating it -- vary widely, but there is no question that corruption, mismanagement, and local capture substantially diminish the impact of international aid and other types of public sector financing.

How can the donor community reduce leakage and increase the impact of aid? Transparency and grassroots monitoring are often cited as powerful remedies. The World Bank's 2004 World Development Report proposes “putting poor people at the center of service provision: enabling them to monitor and discipline service providers, amplifying their voice in policymaking, and strengthening the incentives for service providers to serve the poor." This very simple idea -- that local community members have strong incentives to track how funds are being spent in their own localities, but need detailed public expenditure information and political space to conduct an effective oversight role -- has become increasingly popular. Advocates point to a whole slew of new studies in Kenya, Brazil, Uganda, and India:

- Deininger, Klaus, and Paul Mpuga. 2005. Does Greater Accountability Improve the Quality of Public Service Delivery? Evidence from Uganda. World Development 33(1): 171–191.

- Björkman, Martina, and Jakob Svensson. 2009. Power to the People: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment on Community-Based Monitoring in Uganda. Quarterly Journal of Economics 124: 735–769

- Duflo, Esther, Pascaline Dupas, and Michael Kremer. 2009. Additional Resources versus Organizational Change in Education: Experimental Evidence from Kenya. MIT Working paper.

- Ferraz, Claudio and Frederico Finan. 2008. Exposing Corrupt Politicians: The Effects of Brazil’s Publicly Released Audits on Electoral Outcomes. Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(2): 703-745.

- Gonçalves, Sónia. 2009. Power to the People: The Effects of Participatory Budgeting on Municipal Expenditures and Infant Mortality in Brazil. LSE Working Paper.

- Afridi, Farzana. 2008. Can Community Monitoring Improve the Accountability of. Public Officials? Economic and Political Weekly 43 (42).

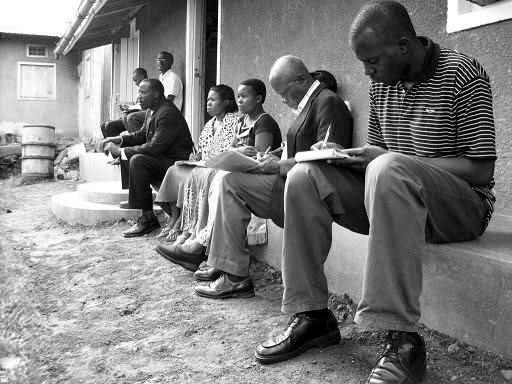

Martina Björkman of Bocconi University and Jakob Svensson of Stockholm University provide particularly compelling evidence. In 2004, they collaborated with the World Bank to design and implement a randomized field experiment in 50 Ugandan communities. "In the experiment, local NGOs facilitated village and staff meetings in which members of the communities discussed baseline information on the status of health service delivery relative to other providers and the government standard. Community members were also encouraged to develop a plan identifying key problems and steps the providers should take to improve health service provision. The primary objective of the intervention was to initiate a process of community-based monitoring that was then up to the community to sustain and lead." Here's what they found after one year:

- Treatment communities became more engaged and more closely monitored their health service providers.

- The practices of health service providers improved significantly in the treatment communities (e.g. increased childhood immunization, improved examination procedures, lower waiting times, lower rates of absenteeism).

- The weight of infants improved and under-5 child mortality declined by 33% in the treatment group.

- Utilization for general outpatient services was 20% higher in the treatment facilities.

However, there are also reasons to doubt the efficacy of social auditing initiatives. Some scholars warn that the process of community monitoring may be subject to "elite capture." John Sidel of the London School of Economics reports that in Indonesia "economic and political power at the regency, municipal, and provincial levels ... appears to be associated with loosely defined, somewhat shadowy, and rather fluid clusters and cliques of businessmen, politicians, and officials." Scott Fritzen of the National University of Singapore has conducted an evaluation of community-driven development initiatives in 250 Indonesian sub-districts and concluded that "elite control of project decision-making is pervasive." Another group of researchers affiliated with MIT's Poverty Action Lab has evaluated community monitoring interventions in India's primary education sector. They find that, despite significant information disclosure, "community members did not know what they were entitled to, what they were actually getting, and how they could put pressure on the providers."

What then should policy-makers, practitioners, and researchers take away from the existing body of literature? Here are our take-aways:

1) Grassroots monitoring does work in some settings and in some cases it can yield enormous development gains.

2) We need more evidence on the conditions under which community monitoring improves development outcomes. For example, it could be the case that grassroots monitoring is more effective in countries with higher levels of internet or mobile phone penetration. It could also be the case that the civil liberties and media freedoms play a role in determining whether there is sufficient "political space" to sound the alarm when service providers are not delivering. There could also be a supply side dimension: Are domestic CSOs with a significant local presence more effective than international NGOs at mobilizing and coordinating individuals? Are donors, local NGOs, and service providers disclosing the right kinds of information in the right formats (posters, newspapers, mobile phones, internet)?

In its newly-released MDG strategy, the Obama administration underscores the importance of "fund[ing] applied research by supporting local, national, and global research networks working on key problems related to the MDGs." This strikes us as a particularly promising area for applied research that could have an enormous impact on MDG goals related to public service delivery.

3) Those of us who are interested in the prospects for crowd-sourcing aid information need to begin asking hard questions about "necessary and sufficient conditions." We'd encourage readers of this blog to keep an eye out for further discussion of what motivates individuals and institutions to crowd-source information. AidData and BYU's Political Economy & Development Lab are hoping to soon launch a randomized control trial that will test some key hypotheses related to crowd-sourcing effectiveness.