The energy sector is developing rapidly in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and is a priority for both governments and international partners. The UN launched the Sustainable Energy for All Initiative with the objectives of achieving universal energy access, doubling the share of renewable energies, and doubling the rate of improvement of energy efficiency by 2030. The US, EU, and China are investing heavily in SSA’s energy sector, raising hopes and sometimes concerns. Chinese President Xi Jinping has promised over $20 billion in infrastructure, farming and business loans. EU member states have pledged to provide energy access for 500 million people by 2030. In June 2013, US President Barack Obama unveiled “Power Africa”, a largely private sector effort to increase generation capacity, improve access for 20 million new households, and give $7 billion in energy financing over five years. Despite these efforts, the International Energy Agency estimates that additional investments of $20 billion yearly are required to meet SSA’s power needs by 2030.

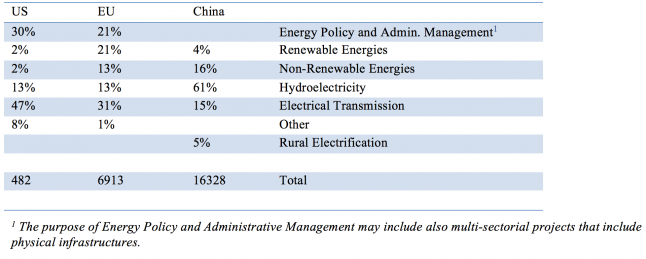

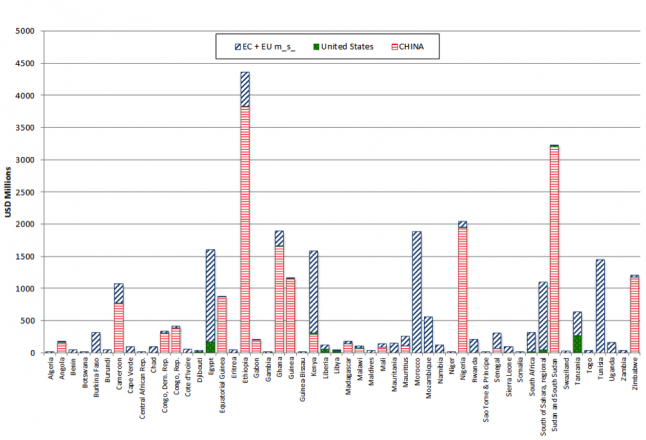

There is a broad view that China has invested heavily, both financially and politically, in Africa over the last few decades, and its influence has risen accordingly. While China does not publish comprehensive data on its official finance to Africa, AidData has pioneered a methodology to collect this information independently. AidData estimates Chinese official finance to Sub-Saharan Africa’s energy sector to be more than $16 billion between 2000 and 2012 (at 2009 constant prices). This makes China the largest development partner in the energy sector with 41% of total commitments, compared to 18% from the EU ($7 billion), and only 1% from the US ($500 million). Chinese development finance also stands out because it is concentrated almost entirely in SSA, while Europe and the US assist also North Africa (41% and 30%, respectively). Additionally, Chinese finance is concentrated on few, high-budget hydroelectric projects, with the largest five representing together 50% of the total commitments, and the total share surpassing 60% (see Table 1). Analyzing the distribution of development finance by country reveals that China is particularly strong in countries with little or no involvement from the EU and the US (see Figure 1).

Table 1. Sectoral Shares of Development Finance for Sub-Saharan Africa’s Energy Sector, 2000-2012

(in USD Millions with 2009 constant prices)

Source: aiddata.org, china.aiddata.org

Figure 1. Energy Sector Development Finance in African Countries from the US, EU and China, 2000-2012

(in USD Millions)

Source: aiddata.org, china.aiddata.org

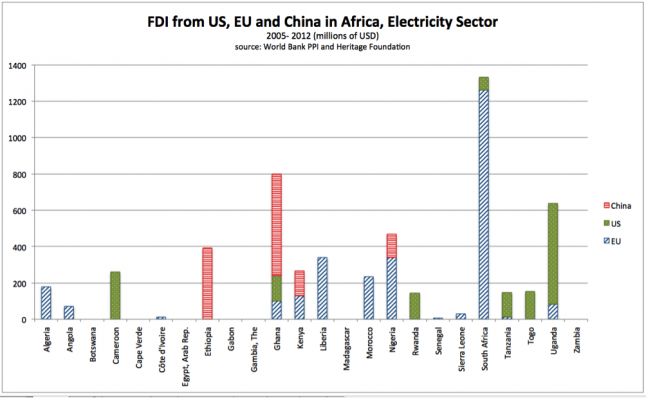

Foreign direct investment (FDI) data is another way to assess the trends. Unfortunately, these data are also scant: granular statistics of FDI per sector and country are not publicly available for China or OECD countries, and analysis is only possible with data collected by third-part organizations or researchers. Considering only the investments in the electricity sector in Sub-Saharan Africa, and combining World Bank and Heritage Foundation data (while doing our best to avoid duplication) my co-authors and I obtained a total figure for 2005-2012 of $2.4 billion from the EU, $1.4 billion from the US, and $1.2 billion from China. According to the data, with few exceptions (like Kenya), there is nearly always a clear dominant player in the energy investments of a specific African country. Of the six countries initially selected for the Power Africa initiative (Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, and Tanzania), the US is the dominant player in only one (Tanzania) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Electricity Sector Investments from the US, EU and China to African Countries, 2005-2012

(in USD millions)

Source: World Bank PPI and the Heritage Foundation

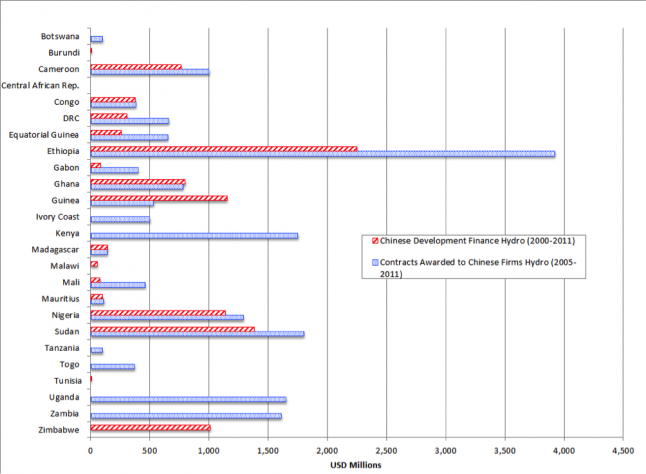

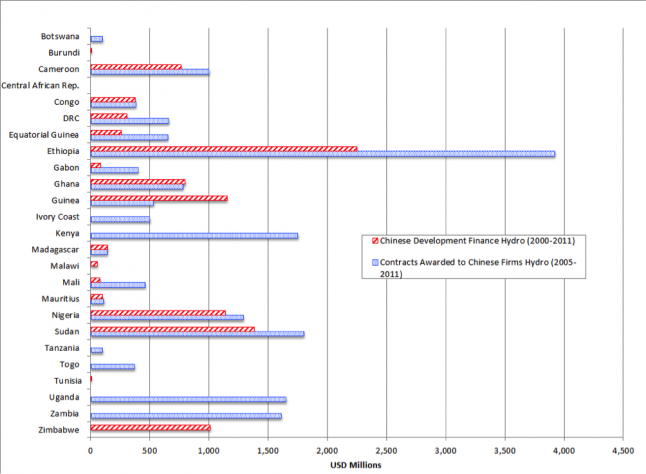

These FDI figures do not include the value of contracts awarded by national governments through competitive bids, though these instruments constitute another major form of economic involvement in the energy sector of African countries. The Heritage Foundation estimates that the value of contracts awarded to Chinese companies for the energy sector to be of more than $18 billion between 2005-2012. Notably, these contracts were all in the hydroelectric sector, showing a clear correspondence with the distribution of Chinese development finance (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Chinese Development Finance and Contracts Awarded to Chinese firms in the Hydroelectric Sector, 2000-2012

Source: World Bank PPI and the Heritage Foundation

These FDI figures do not include the value of contracts awarded by national governments through competitive bids, though these instruments constitute another major form of economic involvement in the energy sector of African countries. The Heritage Foundation estimates that the value of contracts awarded to Chinese companies for the energy sector to be of more than $18 billion between 2005-2012. Notably, these contracts were all in the hydroelectric sector, showing a clear correspondence with the distribution of Chinese development finance (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Chinese Development Finance and Contracts Awarded to Chinese firms in the Hydroelectric Sector, 2000-2012

Source china.aiddata.org and the Heritage Foundation.

Despite shortcomings in the data, international involvement in Sub-Saharan Africa’s energy sector appears to be growing. If SSA is to come close to meeting universal energy access goals by 2030, however, the region will require a broader range of investors, well above the scale experienced to date. Morgan Bazilian, Todd Moss and I have attempted to explore some trends for energy sector investments by three large donor and investor countries. Our preliminary analysis suggests that there is less competition between these countries in many markets than previously assumed.

Still, the scale of total investment remains far below the estimates of current and future demand. There remains plenty of space for all investors. We should be cautious in drawing conclusions about the machinations of policymakers in Beijing, Brussels, and Washington, as they may be driven more by commercial or development objectives than strategic counter-moves. The principal challenge for African policymakers is to manage these giant players in a manner that maximizes investment—and ultimately boosts the generation and distribution of energy to reach the millions currently living without.