On January 12, 2010, Haiti experienced a 7.0 magnitude earthquake, its epicenter approximately 25 kilometers away from the capital, Port-au-Prince. The earthquake resulted in a devastating loss of over 200,000 lives and damage to over 250,000 homes and commercial buildings. Hours after the earthquake, a crowd-sourced web map was created by the popular open source mapping platform, Ushahidi. This crisis map gathered thousands of crowd-sourced SMS and social media posts reporting damage and emergencies and visualized this data in the Ushahidi Haiti Crisis Map. As a result of the mapping, humanitarian intervention forces were able to carry out more targeted, efficient emergency relief.

Since Ushahidi's debut in 2008 following the outbreak of post-election violence in Kenya, crowd-sourced web maps have become a popular tool for humanitarian response. These platforms facilitate an immediate response to the most insecure regions of a country in crisis. These web maps are particularly useful in developing countries affected by disaster, as they rely on simple and commonly used technologies such as cell phones and social media. While these platforms have shown to be effective in targeting short-term humanitarian response, do individual crowd-sourced reports have a long term effect on the allocation of development resources?

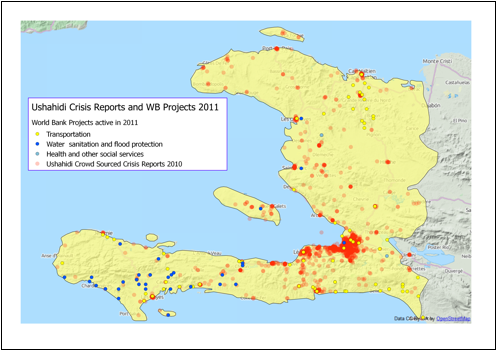

To explore this possibility, I have compared the collection of reports from Ushahidi's web map of Haiti in 2010 with AidData's 2011 geocoded World Bank project data for Haiti. For the World Bank projects in Haiti, I focused on three sectors: water sanitation, transportation, and health services. (NOTE: I excluded the following sectors from this analysis: energy and mining, public administration law and justice, education, finance, agriculture fishing and forestry, industry and trade)

Water sanitation, in particular, has long been a salient issue in Haiti. Prior to the earthquake, the country had the lowest access to improved water and sanitation infrastructure in the Western Hemisphere. In the aftermath of the earthquake, providing clean water to cities and refugee camps lacking in proper infrastructure was one of the greatest challenges faced by humanitarian organizations.

Map created by Sara Rock using data from Ushahidi's Haiti 2010 web map

and AidData's 2011 geocoded data for World Bank projects in Haiti.

In this map, we can see that World Bank projects focusing on water and sanitation are predominantly targeted in the departments of Grand'Anse, Sud and Nippes (all located on the southern peninsula). Transportation aid, which includes infrastructure repair projects, is more evenly spread throughout the country. From the Ushahidi crisis reports, we can see the greatest cluster of reports from the Ouest department, which contained the earthquake epicenter.

This pattern has many possible implications. It is possible that in the aftermath of Haiti's devastating earthquake, emergency relief was provided through NGOs and international charities while, international financial institutions such as the World Bank may have focused on previously established long-term projects. Many of the World Bank projects from AidData's database had been already been active for several years in 2011.

While this comparison only reflects a small facet of international aid, the rise of crowd-sourcing and web mapping technology shows promise to be a powerful tool that can help international organizations, whether small NGOs or international financial institutions, more effectively target aid investments to achieve a higher level of impact and efficiency.