Humanitarian aid has become an increasingly crucial component of the international community’s response to violent conflict. Outflows of humanitarian aid commitments from OECD member states have nearly doubled over the past decade, rising from around US$7 billion in 2000 to US$13.8 billion in 2010. While some humanitarian aid projects simply seek to provide relief for refugees and Internally Displaced Persons, others are interwoven with counterinsurgency efforts seeking to win over “hearts and minds” and detract support from insurgent groups. But recent studies have suggested that aid projects in conflict zones can produce external costs to civilian populations, such as violence.

Dr. Reed M. Wood, a professor at Arizona State University who co-manages the Political Terror Scale, and Dr. Christopher Sullivan, an assistant professor at Louisiana State University, used AidData’s georeferenced datasets to study the relationship between humanitarian aid and violence against civilians by insurgent or government groups. They find that the introduction of aid into conflict zones is accompanied by a rise in one-sided insurgent attacks against civilians, but that there was no rise one-sided government attacks.

What are the incentives for violence?

While in some cases humanitarian aid can suppress violence and bring about more security, in other cases it may also feed civil wars and promote the diffusion of conflict. When examining these trends at the micro-level, it appears as though the presence of aid may spur violence in the local area, a theory supported by Strandow, Findley, and Young in their AidData working paper, Foreign Aid and the Intensity of Violent Armed Conflict.

Insurgent violence against civilians may stem from two different strategies. In the first, insurgents resort to violence in an effort to secure the resources provided by humanitarian aid for themselves. Insurgents predate aid to augment their war efforts, either by using the aid materials themselves or selling them on the black market. Such looted aid can be quite valuable; for example, rebel factions looted around US$20 million worth of aid from aid organizations operating in Monrovia during the Liberian Civil War.

Insurgents may also view humanitarian aid projects as direct challenges to their authority and control over the local area, particularly aid projects that can seen as politically biased, such as “hearts and minds” projects. When aid agencies essentially provide an alternate form of civil structure in large projects such as refugee camps — by providing public goods, services, nominal security, etc. — insurgents view the aid agencies as direct competitors for civilian loyalty. This effectively robs civilians of their neutrality and ability to capitulate to insurgent demands, making them acceptable targets in the eyes of insurgents.

Humanitarian aid projects may also spark violence between legitimate governments and civilians. Projects such as refugee camps sometimes serve as recruitment beds for insurgent groups, and may prove camouflage to insurgents seeking to blend in with the civilian population. Since distinguishing insurgents and civilians can be a time and resource consuming process, some governments may simply choose to target entire camps if they believe them to be of aid to insurgents. However, since governments receiving humanitarian aid are subject to the leverage of donor countries as well as the approval of the public they wish to serve, they very rarely resort to such violence.

Research design and findings

The authors hypothesize that areas receiving larger commitments of humanitarian aid will be subject to more frequent attacks by insurgent and government forces. Leveraging AidData's geo-referenced datasets, they find that the presence of humanitarian aid correlates with an increase in one-sided insurgent attacks on civilians, but not one-sided government attacks.

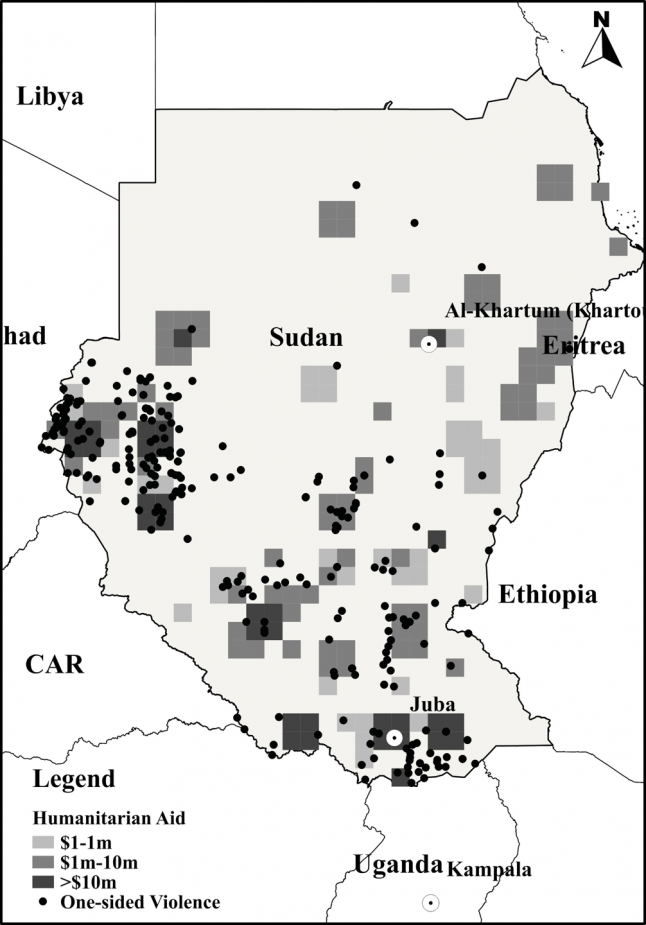

Figure 1: Humanitarian aid and one-sided violence in Sudan

Geographical units that received humanitarian aid saw nearly double the amount of one-sided insurgent attacks against civilians compared with areas that received no such aid (see Figure 1, above) — but the authors found no such rise in government attacks.

This may be because humanitarian aid presents states with an alternative to harsh counterinsurgency strategies, reducing the government’s willingness to target civilians in these areas. States can allow humanitarian aid to address some of the core needs of the population, providing food, medical care, shelter, and other basic services that reduce popular support for the rebels and increase state capacity. When aid succeeds in accomplishing these objectives, government forces may need to rely less on coercion. Aid also provides donors some leverage over the actions of recipient governments, and can serve as an important lever through which donors can influence recipient behavior. Donors can rescind aid when recipients fail to comply with expectations or engage in high levels of violence against civilians.

Wood and Sullivan’s findings give credence to the theory that large-scale humanitarian aid projects in areas of ongoing conflict encourage more local-level violence against civilians by insurgent groups. The authors caution, however, that these negative externalities may be short-lived; it is not known whether humanitarian aid is associated with a rise in violence against civilians over the long term.

As commitments of humanitarian aid to areas of pre-existing conflict continue to grow, understanding how such aid may contribute to local stability or instability is vital to ensuring humanitarian projects succeed. Additional research — on the distinct characteristics of different types of aid projects in relation to how they affect conflict, and other local-level factors such as the pre-existing relationship between aid targets and the incumbent regime — will help illuminate further a heavily debated topic that sometimes generates more heat than light.