This September, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon honored Kuwait for its role as a ‘humanitarian leader’ in the Arab world and beyond. This is just one example of the considerable attention - both positive and negative – that Arab countries have received recently for their aid efforts following the upheaval associated with the so-called Arab Spring.

In the face of such attention, many want to know exactly how much aid Arab countries are giving. Unfortunately, the honest answer is that we don’t know. The existing methods for tracking development assistance developed by the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) aren’t appropriate for measuring Arab aid. Like many other countries in the global South, Arab donors have unique understandings of aid and ways of delivering it that do not necessarily fit into the OECD DAC’s methods. This is likely one reason that major Arab donors like Saudi Arabia and Qatar report only partial information on aid to the OECD, or do not report at all.

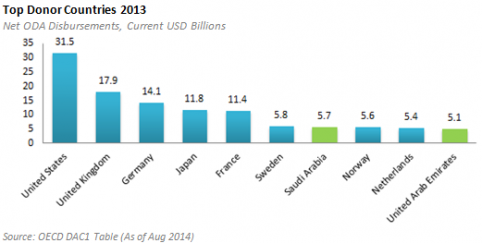

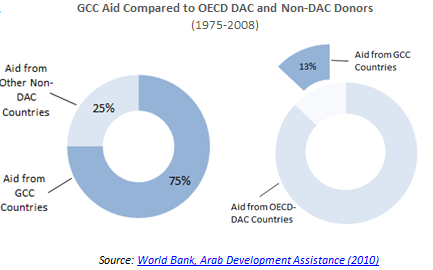

Even with incomplete data, the importance of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) donors is clear. They have historically accounted for the bulk of aid from countries outside of the OECD DAC - 75% from 1975 to 2008. Compared to total aid from OECD DAC donors, Arab donors’ contributions are also significant.

The above graphics make it clear: ignoring Arab countries’ unique understandings and modalities of aid means that we are ignorant about the reality of a significant proportion of modern development finance.

Arab donors are a fairly cohesive, coordinated group. Strong ethno-linguistic, cultural, and religious ties make them relatively more cohesive than other donor groups. Unlike Latin American countries, however, this coordination has not translated into formal consensus around a definition of development cooperation, or a robust methodology that would allow us to systematically measure Arab aid.

Some Arab countries, particularly the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have demonstrated a willingness to work through the existing OECD-DAC framework. The UAE recently gainedparticipant status in the DAC. However, these efforts have not resolved differences between the OECD and Arab countries’ definitions of development assistance, nor established consistent standards for measuring development finance across Arab countries. Instead, the UAE’s reporting framework calculates separate aid figures for what the OECD considers ODA, and for what the UAE itself considers foreign aid.

If we are to more effectively resolve these differences, we first need to identify them. To help contribute to this effort, I’d like to discuss a few of the distinct features that AidData identified while tracking development finance from Arab donors.

Distinct Features of Arab Donors

Public-private aid

The OECD sets a firm division between public and private aid, and only the former is counted towards a country’s ‘official’ development assistance. Whereas Arab countries, particularly major GCC donors , often have a more fluid understanding of public and private aid. This view is informed by their monarchical political systems and distinct understanding of aid and obligations to give. For example, aid institutions that are technically non-governmental may still have close connections to the government as they are often led by royal officials and receive significant funding from official sources. GCC governments also regularly run public campaigns for humanitarian crises, where private donations are mixed with official aid. For these reasons, it is unsurprising that both the UAE and Qatar include foreign aid from non-governmental organizations in their annual foreign aid reports.

Religious Aid

Religiously-affiliated aid from governmental sources is excluded from the OECD-DAC CRS, despite suggestions from non-DAC countries that it be included within Other Official Flows (OOF). Religion is central to how Arab countries understand aid, and a portion of GCC-country aid serves a mix of religious and humanitarian/development purposes. Ignoring the role of religion in aid means neglecting important flows of aid, such as those affiliated with the Islamic practice of Zakat (discussed in a previous First Tranche post). More importantly, it prevents us from fully understanding aid from Arab countries.

Other Issues

Like other South-South Cooperation (SSC) providers, some GCC countries view export support as part of their aid portfolio, based on the idea of mutual benefit. We will discuss the need to reconsider how we understand the role of export support in development finance in a forthcoming post.

Moving Forward

Addressing the issues discussed here will strengthen our understanding of development cooperation, not only as it relates to Arab donors and other SSC providers, but also to DAC donors. For example, other experts have pointed out why we need to reexamine the divide between public and private aid in the context of OECD-DAC countries as well. Recent developments, including the UAE’s new participant status in the DAC, provide valuable momentum for embarking on a meaningful discussion of these issues with Arab donors.